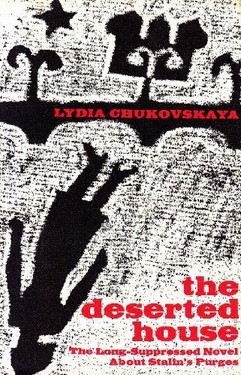

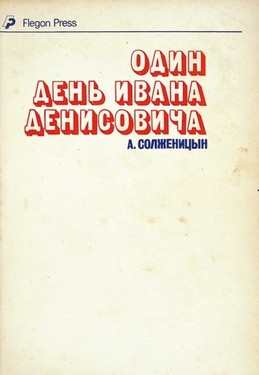

The Deserted House is in some ways a more fascinating description of Stalin’s purges even than Solzhenitsyn’s A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, because the action takes place not in some safely distant camp but in Leningrad, depicting therefore the manner in which the yezhovshchina affected the daily lives of innocently unsuspecting ordinary citizens. It is the story of how a mother attempts to discover why her son, praised in Pravda just a few weeks earlier for his socialist zeal, has been arrested.

The mother, Olga Petrovna, had once belonged to the middle class, but her loyalty to the regime is unquestionable, and when the president of the publishing house for which she works is arrested, she is indignant that a man can be such a hypocrite, for he has masked his fascist beastliness with so apparently decent an exterior. Her son is a Komsomol, and like many members of that purposeful equivalent of the boy scouts something of a prig, readier than most to be vigilant of anti-party activity. His arrest is as much a surprise to the reader as it is to his mother, who stalks off confidently to the Public Prosecutor’s office certain that she will clear up the misunderstanding. It is here that she enters what comes to seem to be not Leningrad but “some strange, unknown city[,”] where a shabby old house one might have passed indifferently a few days before turns out horribly to contain hundreds of desperate women like herself, waiting for days, sometimes weeks, to clear up similar misunderstandings. Here, you give your name to an old woman, curled up on a newspaper on the stairs, who to write it down pulls out a crumpled sheet of paper from her briefcase. From one office you are delegated to another, and each time, before you have succeeded in learning anything at all, an automatic shutter slips down in your face.

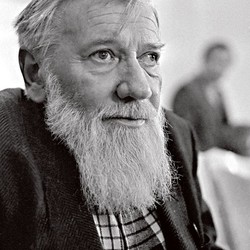

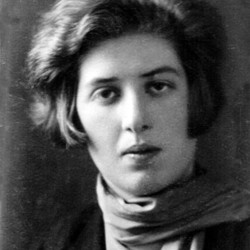

Were it not for the unpretentiousness and simplicity of Chukovskaya’s writing one might be tempted to suspect that she was exaggerating. She is obviously not exaggerating. What comes across most authentically in this book is Olga Petrovna’s loneliness. No one gives her son the benefit of the doubt, so that she must bear among Soviet citizens the unforgivable stigma of treachery. People shun her company because so innocent a faith in Soviet justice has been inculcated into them that they cannot bring themselves to believe that anyone convicted by Soviet power as a fascist beast is not a fascist beast. Others simply use her disgrace to further their own petty aims: her kitchen space, her job and her room are all effectively threatened. And she cannot risk sharing the company of those who are in the same predicament, for them she will surely be arrested for belonging to a counter-revolutionary clique. It is this authentically conveyed despair of loneliness that sets The Deserted House, professionally translated by Aline Werth, far above the normal run of Sovietologists’ fodder. Remarkably, Lydia Chukovskaya, who is the daughter of the best-loved writer in the Soviet Union, tells us that she wrote the book in the winter of 1939–40, with the purge still freshly in her mind, when the mere possession of such a manuscript was a dangerous risk. Recently, she has spoken up bravely in favor of Sinyavsky and Daniel, part of a constant effort on her part which should contribute as much as The Deserted House surely will if it is published in the Soviet Union towards coaxing the revolution back on its proper course. <…>