Prior to 1965, Bulgakov’s fame rested on his novel The White Guard (1924), his notoriety on the novel’s dramatization, Days of the Turbines (1926), which was at first acclaimed, later banned by the censor (1929), and finally (1932), after a personal preview of the production for Stalin, was placed back in the repertory of the Moscow Art Theater. This final incident, with its overtones of behind-the-scenes derring-do and Don Quixotic pursuit of an impossible dream, has long overshadowed Bulgakov’s reputation as a fine dramatist and great prose stylist and satirist. What was once recognized as an eminent talent in such stories as “The Fatal Eggs” and “The Adventures of Čičikov” and in his plays The Crimson Island (1928) and his dramatization of Dead Souls (1932) is now regarded with the appearance of these two novels as one of the great prose-stylists that the Soviet Union has produced. How much more we can yet expect from him lies in the hands of his literary executors and the Soviet censors.

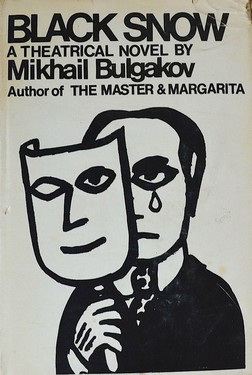

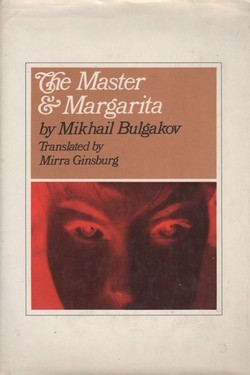

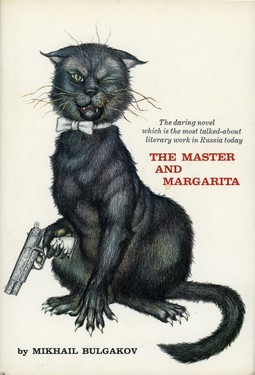

This current exhumation and rehabilitation of M.A. Bulgakov in the Soviet Union invites more than the jubilant and laudatory exhortations that have sounded throughout the world since the publication of Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel in the August 1965 issue of Novij Mir (Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel. Michael Glenny, tr. New York. Simon and Schuster. 1967. 190 pages) and of the inconsistently expurgated version of The Master and Margarita in the magazine Moskva in late 1966 and early 1967 (The Master and Margarita. Mirra Ginsburg, tr. New York. Grove Press, Inc. 1967. viii + 402 pages. — The Master and Margarita. Michael Glenny, tr. New York. Signet Book, The New American Library. 1967. 384 pages). This typical pattern of redemption and resurrection of various writers calls for a closer scrutiny of motives of official censors in a country where nothing ever happens “just so.” As one of the characters in Black Snow remarks: “Your story gives the impression that you are addressing the reader with a sly wink” (p. 177). It is this tone, the “sly wink,” that makes the shorter of these two novels so interesting; for Bulgakov’s Black Snow may mark the beginning of a wave of anti-Stanislavskian criticism in the Soviet Union.

Certainly if change is to come to the Soviet theater, to the traditional (Stanislavskian) staging of even avant-garde plays, a shift of emphasis must occur. During the past four years we have witnessed certain changes, e.g., a freedom among theater people to discuss the accomplishments of past innovators—Tairov, Mejerxol’d, Komissarževskaja. It seems that with the publication of Black Snow, with its highly pejorative depiction of Stanislavskij, an even greater freedom has appeared. In a recent interview Ludmila Saveleva (who portrays Nataša in the Soviet film, War and Peace) made the following remark about her role in the film: “I worked with the book so much that I almost forgot I was Ludmila. But I wouldn’t call it method acting. I know a Russian invented it, but I just don’t think it’s very good” (the New York Times, April 28, 1968, Section D. p. 19). Only time can tell whether Saveleva’s comments will pass into oblivion or whether she will be chastised for her rashness; for, judging by recent events, the intellectuals in the Soviet Union have been properly reprimanded for their outspokenness and are now in a position where they were a decade or so ago. For the time being, further repatriation of writers and artists is extremely doubtful.

Michael Glenny and Mirra Ginsburg are to be congratulated for making these works available to English readers. It its unfortunate that Grove Press chose to publish the expurgated version of The Master and Margarita, for Ginsburg’s translation is as able as Glenny’s. One example will suffice to point out differences in the translator’s style:

Ivan swung his legs off the bed and stared. A man was standing on the balcony, peering cautiously into the room. He was aged about thirty-eight, clean shaven and dark, with a sharp nose, restless eyes and a lock of hair that tumbled over his forehead. (Glenny, p. 133)

Ivan swung his feet down from the bed and peered. A man of about thirty-eight, clean-shaven, dark-haired with a pointed nose, anxious eyes and a lock of hair hanging over his forehead, was cautiously looking in from the balcony. (Ginsburg, p. 148)

Ginsburg follows the Russian syntax more closely than does Glenny, but both capture Bulgakov’s highly dramatic and picturesque description of the “mysterious visitor.”

As for the novel itself, I do not agree with recent critics who assert that, had the novel been published in Bulgakov’s lifetime, it would have instantly been recognized as a classic. It is too derivative of works which preceded it: even had it been published in the Thirties (though one must keep in mind that Bulgakov worked on it all his life, until his death in 1940), the echoes of past masters are evident — Gogol’s Vij, Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, not to mention Joyce, the early Faulkner, Čapek, and Franz Kafka. The book has the smell of age about it. One is reminded of Kataev (The Embezzlers), Ilf and Petrov, Oleša, of the Twenties and Thirties (glorious times though they were), but not of today. Although the novel moves on many levels — satire, allegory, contemporary realia, personal history, philosophical and political commentary — it is never separated from the image of Mikhail Bulgakov — scorned, silenced, ignored, only to be forever resurrected in The Master and Margarita and Black Snow.

The Bulgakov revival has spread beyond the frontiers of the USSR. Shortly after its publication in the Soviet Union, Black Snow appeared in Poland, and Polish monthly, Dialog, has already announced plans to publish The Crimson Island. The Czech journal, Divaldo, and several Yugoslav publications have also shown interest in Bulgakov. Perhaps it is already too late to halt the momentum.

Regardless of Bulgakov’s present fate, he will forever remain an enigma. One senses that the following burst of irony was written in Bulgakov’s last hour: “Oh, that glorious world of the office! Phil — farewell! Soon I shall be gone forever. Think of me sometimes!” (Snow, p. 109). If so, the work takes on another dimension: In that interjection is encompassed a tragedy of a man who gave his life to an institution (the theater) that was wrought with hypocrisy. Forced into the position of literary director of the theater, Bulgakov’s refuge was transformed into a personal Golgotha. Did he in his last hours feel that his life was squandered on a false art?

"