In the world of Po Biz, reputations rise and fall with the strange mercury of celebrity. No man better knows this than Joseph Brodsky, who has refused to make of the vagaries of public whimsey, either here or there, anything but poems. In turn, we would do well to pay our attention to the provenance of his work and not to his biography. The poems themselves, chiefly lyrics, tell us almost everything we need to know. For example, in the translation of Adieu, Mademoiselle Veronique the line “You have been changed to only / a postal address" is footnoted: "The reference is to Mlle. Veronique’s address in Paris". Suppose Veronique were not real: what then? Mr. Brodsky has imagined her into the reality of a poem, and that is adequate. The note is superfluous; the desire for the note is antipoetic.

I find that academic partiality weakens these Selected Poems. In the English I miss that range and variety of style from lyric to dramatic which, as Kees Verheul said in his essay on Mr. Brodsky’s Aeneas and Dido, “seem to have been present from the beginning of his career.” Mr. Verheul especially admired Aeneas and Dido for the “classical simplicity and coherence with which it unites in an ‘objectified’ vision the depth of an intense personal drama with a sense of historical disaster.” Against that large background Joseph Brodsky’s poetry looks different from what, I daresay, most readers take it to be.

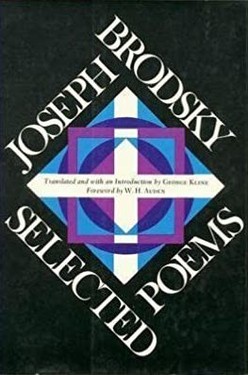

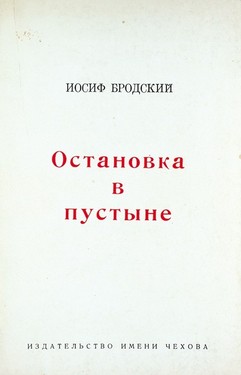

A few of Brodsky’s poems and translations appeared in Soviet and Western magazines in the middle and late ’sixties. Inter-Language Literary Associates in Washington and New York brought out Stikhotvoreniia i poemy (Poems Short and Long) in 1965; Chekhov Publishing in New York issued Ostanovka v pustyne (A Halt in the Wasteland) in 1970. From these two volumes and from later materials George Kline, professor of philosophy at Bryn Mawr, who has known Joseph Brodsky for some years, patiently prepared this volume of translations. Other translators came first, as listed by Professor Kline in his 1971 bibliography of Brodsky’s published work, but none has worked so extensively as he. Carl Proffer, editor of the Russian Literature Triquarterly, where much by and about Mr. Brodsky has appeared, sponsor of Brodsky, translator and explicator of many of the poems, in particular of the long dramatic dialogue Gorbunov and Gorchakov, calls George Kline the Brodsky specialist outside the Soviet Union.

In Selected Poems, the translations and their footnotes seem full of rectitude but lacking poetic rigor. Translating is difficult, I know, and thankless. Readers dump on translators their own peculiar tastes, complaints and whimpers. I mean to be deliberate. (It is both easier and more pleasing to be enthusiastic.) I think these translations are soupy. Because they seem okay, they make Brodsky seem as interesting and as dated as, but less imaginative and resourceful than, Phelps Putnam. In fact, they screen the Russian original from us, neither taking us toward it nor supplying a reliable substitute. George Kline, I know, has read and loved Russian poetry for many years, acquiring a familiarity which, perhaps, has tolerated pedantry and encouraged revisionism. He tends to explain too much, and (mole ruit sua) he adds words, images, intonations and lines which do not exist in the original and which, not surprisingly, change Brodsky’s work. The Selected Poems gives us a notion not of how Brodsky writes but of what themes he writes about and of some of his pictures. The flaccidity and the rhetorical sentimentality come not from Leningrad but from Bryn Mawr.

One of Mr. Brodsky’s most admired and best-liked poems, a poem with which he often concludes his readings, Odysseus to Telemachus, has been unintentionally but unusably padded. For example, Joseph Brodsky begins directly: “My Telemachus.” George Kline begins: “My dear Telemachus.” Kline’s line “Grass and huge stones … Telemachus, dear boy” is not in Brodsky’s poem. Brodsky has Odysseus speak of “wasting time” in Troy; Kline, setting up shop for himself, clobbers the line by reaching for a metaphor to extend the image of death, ends up in the cliché: “killing time.” The lines “To a wanderer the faces of all islands / resemble one another” baffled me – faces? why to a wanderer? Indeed, they are a needless distortion of the clear and suggestive “All islands are alike / when you travel so long,” a reference to the opening

sentence of Anna Karenina. The horizon does not “sting” the eyes; it “stops” them, or “blocks” them. There is nothing about growing “strong”; the poem has “big.” “Pawing bullocks?” No, no “pawing.” “Palamedes’ trick?” Without “trick.” “Blameless dreams”? Why not “sinless” as in the Russian? On we go, adding something to our List of Suggestions from nearly every line or from every two lines, for what in the original is simple and direct. Thus “If not for Palamedes, we’d be together” becomes: “Had it not been for Palamedes’ trick / we two would still be living in one household.” Or take the easily grasped, colloquial thought – “your brain / loses track, counting the waves” which translation has transmuted into – “The mind trips / when it counts waves.” No metaphor is meant; what George Kline introduced is alien. All the notes in the world about “untranslatable puns” cannot overcome false revamping.

That brings me back to the question: how do we judge what we read if we know that it is not (or if we cannot be certain that it is) what was written? Even Pushkin, well and extensively translated by Walter Arndt, exists in a limbo of intellectual generosity, little more than tolerated by English professors. How can any of us know who is Joseph Brodsky?

I would offer judgment, but I cannot assume that you read Russian. Therefore, you have nothing but my word for it, and that, we all know, in literary matters is never enough. If we sat down and read Selected Poems as we would read, say, William Heyen’s Noise in the Trees (both poets are the same age) or Robert Siegel’s The Beasts and the Elders (Siegel is a year older, if that matters), what would we learn? What if we compare Joseph Brodsky’s work to that of Ivan Elagin? I mention the names of these good poets only to try to stop the nonsense of parking Brodsky in the academically certified pantheon of Russian poets: “Like Mandelstam and Tsvetayeva, Brodsky makes skillful and extensive use of Greek mythology” (from George Kline’s introduction). In fact, lots of poets use Greek mythology – lots of Russian poets.

Brodsky is an extremely sensitive, alert, skilled, independent, and suggestive poet from whose work I discover something each time I come to it. He is not a trained bear, and I see no need to exhibit him as one or, parasitically, to feed his celebrity. I think that those who read his Russian poems will find in them a dignity, a grandeur, and a sadness deeply reflective of Russian culture and of our own world. This edition of Selected Poems is one of the best reasons I know for printing the original facing the translation. Had that been done, many of Brodsky’s poems would have been widely available and gratefully read. About that I remain enthusiastic.

"