FROM THE PUBLISHER

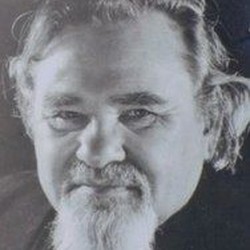

ВІД ВИДАВНИЦТВА 1950-60-х роках, в добу післясталінської духовної відлиги, в Україні з’явилися три п’єси, в яких були зроблені більш чи менш спроби розкрити злочини радянської влади. Це були: «Крилля» О.Корнійчука (1954), «Мовчати заборонено» М.Вінграновського (1955) і «На дні морському» М.Руденка (1960). У свою чергу з’явилися в Москві: «Відлига» І.Еренбурга, «Не житиє свиням» В.Дулінева й «Один день із життя Івана Денисовича» О.Солженіцина. Ні в безпеченій тоді ідейно твори ті були однаково страшні. Вони пробили шпарину в панцирі нав’язуваних ідеологічних догм. Можливо, найбільш несміливим з них був твір під назвою «Крилля» О.Корнійчука. Та й він все ж показував хоч і фрагментарно, як людина може стати жертвою репресій з боку «органів». Хоч п’єсу «Крилля» в «Молодій гвардії» (видавництво «Молода гвардія» — прим. ред.) знищили, вона «пішла в народ». А от «Мовчати заборонено» вже мало свою історію, більш страшну і трагічну. Миколу Вінграновського було примушено «добровільно відмовитися» від твору та «нехай щастить!». В результаті п’єса була викинута з літературного процесу. Пізніше, після повернення з Росії, автор знищив її рукопис. І тільки випадково у студентській газеті «Комсомолець Полтавщини» на першій сторінці була надрукована стаття «Творіть пісню, поети!», в якій ішлося про майбутню п’єсу Вінграновського — «Мовчати заборонено». А коли автор з’явився до видавництва «Радянський письменник» з рукописом п’єси, то йому вже сказали: «Ви молодий, у вас все попереду!». Тільки, зважаючи на його впертість, п’єсу спочатку ухвалили, а потім зняли з друку і автора «списали». своїх заблукалих у хащах минулого, хоч, може, внутрішньо все-таки. Саме цей залякуваний і тяжкий комплекс «батьків-дітей» створює найбільшу трагедійність ситуації в драмі М.Руденка. І в цьому, нам видається, її велика мистецька сила. На істинному шляху правди Миколи Лугового (героя драми) було ясно, що злочини сталінської доби мусять бути покарані. Але зрозуміло йому й те, що справедливості на світі, зіткнувшись з правдою минулого, мусіє зникнути. Не якось іронічно звучить ця паралеля до долі самого автора драми. Хіба вона не стала теж трагічною? Автор «На дні морському» поклав на кін своє життя за правду і справедливість. Микола Руденко пройшов катівні ГУЛАГу, був поневірянцем і криголамом опору тоталітарному режимові, як і його персонажі. Так само своїми людськими почуттями й душею заявив про необхідність покарання злочинів сталінізму український Гельсінський рух, що з’явився після оприлюд- нення правди про Голодомор 1933 року. Крім Миколи Руденка, в цьому русі діяли такі особистості, як Петро Григоренко, Олесь Бердник, Микола Рудь, В’ячеслав Чорновіл, Василь Стус, Олекса Тихий, Левко Лук’яненко, брати Горині, Юрій Шухевич, Юрій Бадзьо та інші. З’явилося слово правди, якого так боялася імперська комуністична система. І почався її розпад. «На дні морському» — це такий самий, як «Один день Івана Денисовича», акт звинувачення комуністичного режиму. Поки що, на жаль, у нас ще не прийнято виносити історичні вироки катам, які безневинно розстрі- лювали, мордували, вбивали кращих із кращих і тягли до свого безіменного лігвища... безодню минулого. Ті строго їх судили. Можливо, суворіше, ніж вони того заслуговують. Бо судили не з того рубежа, з якого вони колись вийшли, а з того, куди прийшли. Їхні стомлені очі бачили такі страждання, які тобі й не снилися... І знов починаються розіп’яті про голодні роки і розруху, про те, як твої одноплемінці падали грудьми на амбразури ворожих дотів. Тебе глибоко обурює невмирущий сумнів у вірності великим ідеалам. Ти не спиш ночами, тяжко караєшся. А, заснувши, вриваєшся у сни почвари, тим, хто карався... — Неправда, неправда! І вранці, зіщуливши зуби, гупаєш своїми кулаками у немічне, хоч і бородате, обличчя супротивника і під його скажений стогін будишся зі сну. Що це було? Битва тіней, виклик кривавій плоті й крові тоталітаризму? Чи нове слово, народжене у безсонні? Це вже було в історії. Старі люди, які ще пам’ятають війну, кажуть, що до них у снах приходили тіні загиблих. Вони йшли, обпалені вибухами, поранені, безрукі, безногі, безокі, як з якихось середньовічних страшних сновидінь, і заглядали в очі живим, вимагаючи справедливої помсти. Ішли й ішли звідусіль, з’являючись з-під уламків, зі схованок, з окопів. Вони йшли в безодню минулого. Ті строго їх судили. Можливо, суворіше, ніж вони того заслуговують. Бо судили не з того рубежа, з якого вони колись вийшли, а з того, куди прийшли. Їхні стомлені очі бачили такі страждання, які тобі й не снилися... І знов починаються розіп’яті про голодні роки і розруху, про те, як твої одноплемінці падали грудьми на амбразури ворожих дотів. Тебе глибоко обурює невмирущий сумнів у вірності великим ідеалам. Ти не спиш ночами, тяжко караєшся. А, заснувши, вриваєшся у сни почвари, тим, хто карався... Українське В-во «Смолонські», випуск Х. В. Симоненка

FROM THE PUBLISHER In the 1950s-60s, during the period of post-Stalinist spiritual thaw, three plays appeared in Ukraine that made more or less an attempt to expose the crimes of the Soviet government. These were: Wings by O. Korneychuk (1954), Silence is Forbidden by M. Vingranovsky (1955), and At the Bottom of the Sea by M. Rudenko (1960). Around the same time in Moscow, there appeared The Thaw by I. Ehrenburg, Not by Bread Alone by V. Dudintsev, and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by A. Solzhenitsyn. None of these works were ideologically safe at the time; they all posed a threat. They managed to crack the armor of imposed ideological dogmas. Perhaps the least daring of them was Wings by O. Korneychuk. Even so, it still depicted, albeit fragmentarily, how a person could become a victim of repression by the “organs” (Soviet security agencies). Although Wings was destroyed by the publishing house Molodaya Gvardiya, it “found its way to the people.” But Silence is Forbidden had an even more tragic history. Mykola Vingranovsky was forced to “voluntarily renounce” the work with a cynical farewell: “Good luck to you!” As a result, the play was removed from the literary process. Later, after returning from Russia, the author destroyed his manuscript. Only by chance did an article titled Create Songs, Poets! appear on the front page of the student newspaper Komsomolets of Poltava, mentioning Vingranovsky’s planned play Silence is Forbidden. However, when the author brought the manuscript to the Soviet Writer publishing house, he was told: “You are young, you have everything ahead of you!” Initially, the play was accepted, but later it was withdrawn from publication, and the author was “written off.” The deeply ingrained and burdensome “parent-child” complex creates the greatest tragedy in M. Rudenko’s play. And in this, it seems to us, lies its great artistic power. For Mykola Luhovyi, the protagonist of the drama, it was clear that the crimes of the Stalinist era must be punished. However, he also realized that there were no conditions for this just act yet. Confronting the dead wall of silence, he had to perish. This, in some way, mirrors the fate of the play’s author himself. Isn’t his fate also tragic? The author of At the Bottom of the Sea staked his life for truth and justice. Mykola Rudenko endured the torture chambers of the Gulag, suffered exile, and broke through the walls of totalitarian oppression, just like his characters. Similarly, with his feelings and soul, he declared the necessity of punishing the crimes of Stalinism. The Ukrainian Helsinki Group, which emerged after the truth about the Holodomor of 1933 was revealed, was born in the same struggle. Apart from Mykola Rudenko, this movement included figures such as Petro Hryhorenko, Oles Berdnyk, Mykola Rud, Vyacheslav Chornovil, Vasyl Stus, Oleksa Tykhyi, Levko Lukianenko, the Horyn brothers, Yuriy Shukhevych, Yuriy Badzo, and others. A word of truth emerged, which the imperial communist system feared so much. And so, its collapse began. At the Bottom of the Sea is just as much an indictment of the communist regime as One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Unfortunately, we have not yet reached the point of passing historical verdicts on the executioners who shot, tortured, and murdered the best of the best, dragging them into their nameless lair… The abyss of the past. You judge them strictly. Perhaps even more harshly than they deserve. Because you judge them not from the standpoint of where they came from, but from where you have arrived. Their weary eyes saw suffering that you could not even imagine… And once again, the stories begin—of the years of famine and devastation, of how your fellow countrymen threw themselves onto the embrasures of enemy pillboxes. You are deeply troubled by the persistent doubt in the loyalty to great ideals. You lie awake at night, tormented. And in your sleep, you cry out: — It’s not true, not true! And in the morning, clenching your teeth, you pound your fists into the unknown, trying to break through to the truth. Because no pretense of truth satisfies you… It is difficult to shake off the burden of suffering and the bitter experience shaped in ways incomprehensible to you, filled with pain and joys. Could you truly understand with your heart, with your own blood, what it means to survive on one hundred grams of bread per day? Born of harsh circumstances, doubts drove Mykola, the protagonist of At the Bottom of the Sea, to death. But there was no other way out for him. His path was the path of an entire generation that believed, adapted, renewed itself, and gained insight. And they paid dearly for that insight. Mykola Rudenko and his generation wanted to believe that in new novels and plays, there would be no place for such tragic figures as Mykola and his mother from At the Bottom of the Sea. But the past few years have shown that in real life, in today’s Ukraine, they still exist. This was the reason why At the Bottom of the Sea was never staged again, was never published, and why its author, an unyielding truth-seeker, continues to suffer severe repression even today. Ukrainian Publishing House “Smoloskyp” Named after V. Symonenko