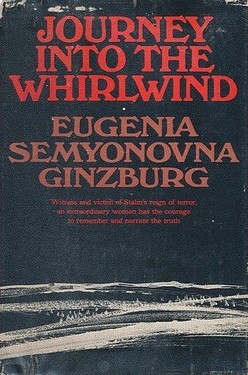

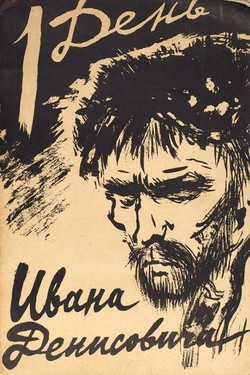

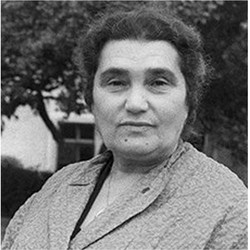

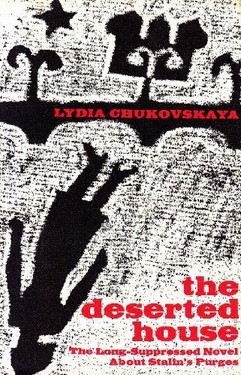

After the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s now famous One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich Soviet publishers have received thousands of manuscripts of memoirs on deportation, novels, accounts of all sorts which are dealing with an era that has been described somewhat euphemistically as “the cult of personality.” Among these manuscripts there is one novel, written by a distinguished and well-known author, Lydia Chukovskaya. It dates back to 1939 but she kept it tucked away in her desk drawer at great risk and danger to herself for more than twenty-five years. There is also a voluminous chronicle of purges and deportation during the years of 1930-1940, written by Evgenia Ginzburg, who is not a literary figure but was well known in the hierarchy of the party to which she belonged at one time. All these manuscripts remained unpublished because highly placed officials in Moscow considered it inappropriate to publish these documents which are embarrassing for the regime.

After having circulated in Moscow in manuscript or mimeographed form the books of these two women authors were published in the West, first in the original Russian, later translated into various other languages. The reviews were unanimously favorable. Both works were praised for their literary quality and were described as informative and disturbing masterpieces of contemporary Russian literature.

“All this resembles a nightmare,” wrote one critic who was well acquainted with the realities of the Stalin period, in the margin of Ginzburg’s book. Yes, one thought to know, if not everything, then at least the most essential horrors of Stalin’s regime. Yet, this Kafkaesque castle turns out to be an inextricable labyrinth. Each witness reveals new and unexpected aspects of it. This is why the books by Chukovskaya and Ginzburg constitute invaluable first hand source material for historians who are often unable to get access to the actual documents. Authoritative beyond doubt, they fill many a gap in the documentation of the period.

To be sure these two works differ greatly from one another in character as well as style. In the case of Chukovskaya we have a fine and sensitive novel whose fictitious characters are plunged into real life situations. Evgenia Ginzburg gives us her memoirs of ten years of Stalinism, the early part of which she spent atop the party hierarchy, the latter as a deportee. The milieu described by these two women also differs considerably. Olga Petrovna Lipatova, the heroine of Chukovskaya’s novel, is an obscure Soviet woman, top typist in a publishing house; Evgenia Ginzburg, on the other hand, who is telling her own story, once belonged to the party elite. Even so, it’s the same Odyssey.

And it is not the topic alone which invites comparison of these two books. As sensitive and good observers these two authors describe not only life during the same era but in both books the protagonists are loyal, uncompromisingly devoted Soviet citizens. Ginzburg adds furthermore a special dimension to her biographical testimony. She is somehow “typical” for the new post-revolutionary generation of communists. First a member of the Komsomol and later of the Party, she was professor and propagandist in Kazan and became wife of P. Axionov, a member of the secretariat of the regional party of Tartary and also of the Central Executive Committee of the U.S.S.R. All this made her a member of the “new bourgeoise.” At this time she was a true unquestioning Stalinist who moved in the highest party circles and enjoyed special privileges on account of her husband’s position. In February 1935 all this came to a sudden end and her Calvary began. Without the slightest notion as to what had happened she was accused of all the capital sins and was trapped by the infernal machine of moral torture, arrest, condemnation and eventually deportation.

We find in these two books a convincing and truthful evocation of the general atmosphere of the time, an exact description of the mechanism of accusations and tortures. While Chukovskaya engages in fine psychological analysis, Ginzburg gives a minute and factual account of her own vicissitudes and those of others who travelled with her from station to station on the road to Calvary. Her memoirs have unusual richness and depth and abound in unknown information which requires extensive scholarly study and interpretation. For her point of view is influenced by certain deformations and conditioned reflexes of an ex-party functionary, a fact that confers authenticity upon her observations and dramatic power upon her reflections. Both works are moving human documents of literary value and at the same time essential sources for the understanding of the Stalin period.

The task of Paul Stevenson and Max Hayward - Ginzburg’s translators - was not an easy one. The Russian edition which was published in Italy was full of printing errors which sometimes distorted the meaning. Even worse, the author’s style is that of writers between 1920-1930, notably authors like Pilniak and Babel. The prison jargon and camp lingo which Ginzburg uses felicitously, are also creating translation difficulties. Even so, Misters Stevenson and Hayward have done an excellent job. One would have liked to find some critical or explanatory notes to facilitate the understanding of the less informed reader or the hurried researcher. A critical and annotated edition of the Ginzburg book would be an important contribution and would deserve a special place among the books on the reading list for basic university courses on the U.S.S.R.

George Haupt

Ecole des Hautes etudes

Centre de Documentation sur L’USSR et les Pays Slaves, Paris