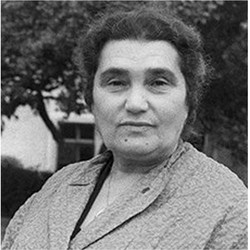

On Dec. 1, 1934, Eugenia Semyonovna Ginzburg was 27 years old, the mother of two young children, wife of a local Communist party official in the Volga River city of Kazan, a teacher, a worker on the local newspaper, Red Tartary, and unfortunately, a dedicated, loyal, principled member of the Communist party.

Had she not been a member, she might have lived out her life with no more misfortune than was the lot of most Russians who came to adulthood under Joseph Stalin. True, she probably would have lost her husband, since he was a member of the Tartar Province Committee of the party and most officials of his rank were purged. But she might have escaped with a few months of arrest, the loss of her job, relegation to some menial employment, difficulties of housing, and reprisals against her children.

What led Eugenia Semyonovna Ginzburg to prison, into 18 years of life in the terrible “isolators,” Siberian cattle-car convoys, transit camps, brutal work in the Kolyma forests, starvation, torture, degradation and sufferings beyond belief? It was the fact that she was a party member so loyal, so dedicated, so principled that she could not conceive of the deceit, hypocrisy, sadism and corruption brought into Soviet life by Stalin.

On that fateful Dec. 1, 1934, when at a hastily summoned 6 A.M. party meeting she first heard the news of the assassination of Sergei Mironovich Kirov, the party leader of Leningrad (the event which triggered Stalin’s purges), Mrs. Ginzburg recalls: “I must say in all honesty that, had I been ordered to die for the Party – not once but three times – that very night, in that snowy winter dawn, I would have obeyed without the slightest hesitation.”

Thus, when the inevitable charges, false and stupid, were brought against her, she did not recant and demean herself (which would have ended the matter). She angrily denied her guilt. Step by step she marched to her fate, head high, clad in the anger of her righteous party belief. When her old peasant mother-in-law urged her to slip away to the country and get out of sight, she haughtily rejected the notion. When a young Communist wisely urged her to join him in “going to the gypsies” for a year or two until the dust settled, she was outraged.

Not until 1937, when she had begun to live the life of thousands of her fellow party members, first in the Black Lake prison in Kazan, then in the central Lubyanka prison, in the vast Butyrki prison, Lefortovo prison in Moscow and the Korovniki prison in Yaroslavl, did the incredible truth finally become plain to Mrs. Ginzburg: that it was Stalin and the party to which she had dedicated herself that was now ravaging the country.

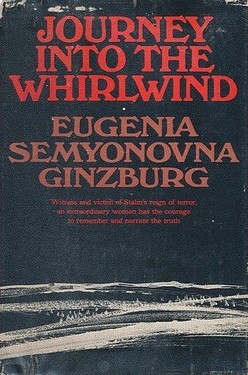

No account yet come to light matches the honest poignancy of Mrs. Ginzburg’s story. Literary treatments of Stalin’s terror have been appearing since the 1930’s, and the best fictionalization is probably still Arthur Koestler’s masterly psychological polemic Darkness at Noon. But Koestler’s imaginary scenes in the interrogation cells of the Soviet prisons seem pallid beside the reality of Mrs. Ginzburg’s narrative. Not even Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich matches it.

One work which may well be read as supplemental to Mrs. Ginzburg is Lydia Chukovskaya’s haunting narrative of a mother’s anguish in Leningrad with her son – also, of course, the staunchest of young Communists – is caught up in the terrible machine of the purges. Lydia Chukovskaya tells the story from the viewpoint of one who is left behind, Mrs. Ginzburg as one who was caught up in the very maelstrom of the terror.

How Mrs. Ginzburg survived the physical torture, the starvation, the dysentery, the beatings, the icy, windowless punishment cells, so narrow that the victim was virtually buried alive, the brutality of the thieves, murderers and prostitutes with whom the “politicals” were deliberately mixed, the psychological weight of isolation and hopelessness is a monument to the grandeur of the human spirit.

Through the tale runs the fantastic consistency of Russian life. Mrs. Ginzburg and many of her fellow women prisoners were buoyed by the heroic example of the wives of the Decembrists, who followed their noblemen husbands into Siberian exile under Nicholas I, and by the flaming words of Vera Figner, the revolutionary girl who survived 20 years in the Schlusselberg fortress of St. Petersburg after the assassination of Alexander II in 1881.

The prisons in which Mrs. Ginzburg and the others were held, in many cases, were the same which had confined generations of rebels against Czarist tyranny. In the prison camps there were hierarchies of victims – the earliest being Mensheviks arrested when Lenin was still alive, members of the Socialist Revolutionary party, early oppositionists of the 1920’s and the early 1930’s.

The terror came to a culmination under Stalin. But it had never been absent from Russian life. It is now 14 years since Stalin’s death brought an end to the paranoid world he created. It is 11 years since Nikita Khrushchev stood before a secret session of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party and spread forth the general details of Stalin’s crimes. Russia’s atmosphere has changed incredibly. When Mrs. Ginzburg put down her story, she thought of it in terms of a letter to her grandson. She thought that when he was 20 years old in 1980 it would be possible to publish her appalling story.

“How wonderful,” she writes, “that I was mistaken, and that the great Leninist truths have again come into their own in our country and Party? Today the people can already be told of the things that have been and shall be no more.”

Would that those words were true! Mrs. Ginzburg is active in literary comment and criticism in Moscow these days. Her articles appear regularly in Novy Mir and Literaturnaya Gazeta. The publication of her memoirs apparently had been expected this year in Moscow. The rights to publish the manuscript abroad were contracted in a normal fashion, it was said, by the Moscow literary agency with the Italian house of Arn[o]ldo Mondadori, which in turn sold rights for publication in France, England and now in America. But so far it has not yet been published in Mrs. Ginzburg’s own Russia.

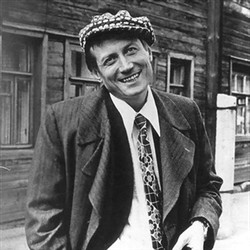

However, there is hope that soon it may appear. Her son, the distinguished young novelist, Vasili Aksyonov, expressed confidence a month or two ago that his mother’s story would be published in the Soviet Union. His opinion was shared by a half-dozen other leading literary figures, both young and old. “It must be published,” one of them said. “Until we tell these stories freely and without censorship we cannot be certain that they will not happen again.”

It is not for nothing that Mrs. Ginzburg’s book bears on it’s fly sheet a quotation from Yevgeny Yevtushenko: “And so I appeal to our government: double it, treble it, the guard on this grave.” The grave he spoke of was Stalin’s. The fear he expressed was that Stalin’s spirit might walk again.