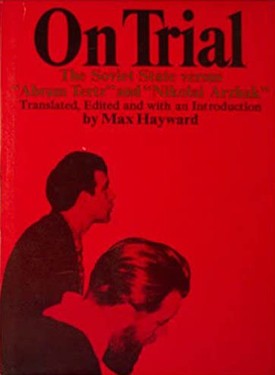

This is a disturbing book. It is a reminder that the Soviet Union, despite its obvious industrial and technological accomplishments, has yet to guarantee to its intellectuals that measure of freedom of expression which affords them the right to publish social and political criticism in a nonconforming, unorthodox literary style. Siniavskii and Daniel, Soviet citizens who published abroad under the pseudonyms Tertz and Arzhak, were arrested in 1965, charged with the crime of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, a violation of Section 1 of Article 70 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR, tried, convicted, and sentenced to seven and five years, respectively.

In this slim volume Professor Max Hayward has ably translated the transcript of the trial, a manuscript which arrived in the West, as Hayward explains in his informative and well written Introduction, “by undisclosed channels, but [which] is of indubitable authenticity,” consisting quite probably of shorthand notes taken by an unnamed spectator at the trial.[1] An appendix to the volume offers the translation of an article by Zoia Kedrina which appeared in the January 22, 1966, issue of Literaturnaia gazeta. Mme. Kedrina appeared at the trial as a kind of “expert” witness for the prosecution, repeating in essence the same hostile opinions of Siniavskii and Daniel that she expressed in the article. As Siniavskii emphasized in his final plea, this case represents the first instance in the history of Russian literature of a writer’s criminal prosecution for what he has written. The past is replete with instances of vilification, imprisonment, banishment, or execution of writers, but never has criminal punishment been handed down by a court of law after a trial at which the defendant’s literary product was the basis for the indictment and formed the principal evidence relied upon by the prosecution. The defendants in this case published abroad without the permission of the Soviet authorities. This is not a criminal offense per se under Soviet law, however unethical it may seem to some observers. The statutory crime for which Siniavskii and Daniel were prosecuted, anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, requires proof of a specific intent, namely, the intent to undermine or weaken Soviet authority. At the trial both defendants disclaimed any such intent, resting their defense on two principal grounds: (1) Their literary work was not anti-Soviet; (2) even if, in the opinion of the court, it was indeed anti-Soviet, the defendants lacked knowledge of this fact.

The prosecution quoted excerpts from the writings of Siniavskii and Daniel, called them “anti-Soviet,” and asked whether the defendants were not of the same opinion. What ensued was perhaps the most fascinating, yet frustrating, part of the trial transcript. Siniavskii and Daniel labeled their works “literature,” devoid of political content. The principal examination proceeded on two levels: the prosecution, possessed by the idea that all literature is propaganda, either pro-Soviet or anti-Soviet, was talking about “slanderous, blasphemous, and sacrilegious fabrications which defame the USSR, its social and political system, and its people”; the defendants, alienated from the hypocritical and superficial reality of their social milieu, viewed themselves as hostile witnesses to their environment and referred to their works as literature containing a human message written in an unorthodox style about subjects which were, but which should not be, taboo. The prosecution accused the defendants of a crime against the Soviet state; the defendants admitted to the breaking of literary taboos. As Siniavskii maintained, “the political characterization of a literary work is a tricky business” (page 126). Tricky, perhaps, but the Soviet court mastered the trick. “Now,” as Svetlana Alliluyeva has noted, “you can be tried for a metaphor, sent to a camp for figures of speech!”

The Soviet statute which was used to send Siniavskii and Daniel off to a labor colony would be declared unconstitutional in the United States as a violation of the Fifth Amendment, which requires that vague laws must be declared invalid and ambiguous ones narrowly construed. Substantive First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech and of the press protect our writers from criminal prosecution for what they have written, provided the literature is not obscene, libelous, seditious, or in some way unduly obstructive of the administration of justice. Even if otherwise valid, the conviction of Siniavskii might well be reversed by a United States appellate court because of the state's refusal to permit him to obtain evidence which he believed necessary in order to present his defense. But such comparative comments are of small solace to Siniavskii and Daniel, who have paid the price for nonconformity. Their conviction will have a chilling effect on other Soviet writers. As Hayward concludes (page 36): “The literary vocation is still considerably more hazardous in Russia under the Soviet regime than it was under the Czarist regime.”

Joseph J. Darby

University of San Diego

School of Law

[1] The original Russian manuscript, with an introduction by Boris Filipoff, has been published under the title Siniavskii i Daniel' na skam'e podsudimykh (New York, 1966).