An émigré approaches a publishing house and claims to be a poet whose works were not allowed to be published in his native country for political reasons. But is the lack of credentials and demonstrated salability a matter of social injustice in his former country, or is it a matter of deficient poetic quality? And what portion of the quality, judging by the poems themselves, is culturally determined in such a way as to render the poems inappropriate to the new social context? France’s new Third Wave publishing house has made the answering of these difficult questions its own particular bailiwick.

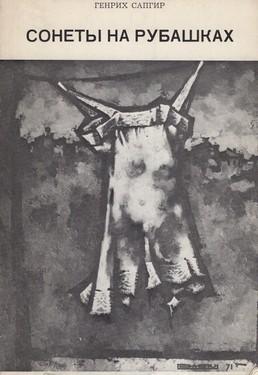

Genrikh Sapgir is a poet with considerable previous exposure who got himself in trouble with the Soviet authorities for writing two sonnets, “Body” and “Spirit,” on two old shirts and hanging them, one above the other, at an exhibition of “left” artists at VDNX. This seemingly innocuous act enabled the authorities to focus their censure on him for his choice of themes as well. In the “Sonnets on Shirts” here, for example, he puns about the “male member” and recalls taking as a souvenir of Yelabuga “the forged blue nail on which Tsvetaeva hanged herself.” There is much emphasis on the “I” of the poet, and much of the poetic commentary seems flip in tone; but the observations are fresh and sometimes thought-provoking. The sound texture of the poems is often dramatic and would surely provide excitement under proper declamation.

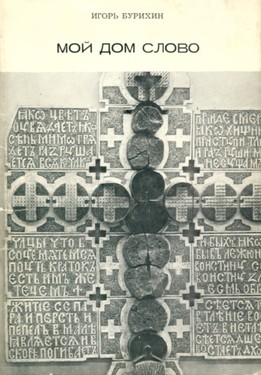

Igor Burikhin’s verse has never been printed by Soviet organs. His poems appeared, however, in various underground publications in the Soviet Union and in émigré journals in the West even before his emigration. A more abstract note is sounded in them. He dwells on the resting place of the soul and ponders immortality as did Derzhavin, saying “No, entire I will not die.” “The word,” as the title of this little collection says, is his “house,” which gives him the power to say: “Let death come. My house blooms in beautiful despair. My house stands at the beginning of a new being.” With these collections, each of which thoughtfully includes a frontispiece photo of the poet and an editor’s introductory notes, one would have to say that Third Wave is off to an auspicious start.

Эмигрант приходит в издательство и заявляет, что он поэт, чьи работы не допустили к печати в его стране по политическим причинам. Но является ли такой статус и продемонстрированный спрос вопросом социальной несправедливости в его бывшей стране, или же дело в недостаточно высоком качестве самих стихов? И какая часть качества, судя по стихотворениям, культурно обусловлена – так, что стихотворение становится неподходящим в новом социальном контексте? Новое французское издательство «Третья волна» сделало ответы на эти вопросы сферой своей частной компетенции.

Генрих Сапгир – поэт, уже сделавший себе имя, но обрекший себя на неприятности с Советской властью, написав два сонета «Тело» и «Дух» на двух старых рубашках и вывесив их, одну над другой, на выставке «левых» художников на ВДНХ. Этот, казалось бы, безобидный поступок дал повод властям применить к нему цензуру, в частности, в отношении его выбора тем. Здесь, в «Сонетах на рубашках», к примеру, он вставляет каламбур о «члене» и вспоминает, как привез в качестве сувенира из Елабуги «гвоздь кованный и синий, на котором Цветаева повесилась». На «я» поэта делается большой акцент, и изрядная часть поэтической рефлексии кажется противоречивой по тону; но наблюдения свежи и иногда наводят на размышления. Звуковая текстура стихотворений часто драматична и наверняка пробудила бы волнение при должной декламации.

Стихи Игоря Бурихина никогда не публиковались советскими органами печати. Его стихотворения, однако, появлялись в различных андерграундных изданиях в Советском Союзе и в эмигрантских журналах на Западе ещё до эмиграции автора. Тон его стихов более абстрактен. Он подробно останавливается на вопросе пристанища души и размышляет о бессмертии, как это делал Державин, говоря: «Нет, весь я не умру». «Слово», как гласит название этого маленького сборника, является его «домом», что дает ему силы сказать: «Пусть приходит смерть. Мой дом цветет в отчаянии прекрасном. Мой дом стоит в начале бытия».

Опубликовав эти сборники, каждый из которых предусмотрительно содержит фотопортрет автора на фронтисписе и вступительное слово редактора, Третья Волна, можно сказать, ярко заявила о себе.