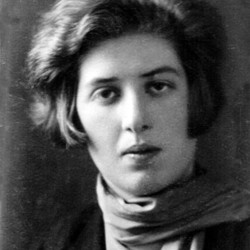

«Он был удивительно противоречив для меня, этот последний год моей первой жизни, оборвавшейся в феврале 1937-го», пишет Евгения Семеновна Гинзбург в своих воспоминаниях, изданных недавно в Милане на русском языке под названием «Крутой Маршрут». Эта «хроника времен культа личности» описывает ее вторую жизнь, в которой рядовая коммунистка Гинзбург превращается из «молота в наковальню».·

«Крутой Маршрут» заставляет вспомнить о ранее изданной в Париже книге Лидии Чуковской «Опустелый Дом». На первый взгляд, как далек крестный путь коммунистки Евгении Семеновны от душевных мук обывательницы Ольги Петровны! Первая жертва активная, вторая – пассивная. Обе они – матери, но в то время как Ольга Петровна страдает только из-за любви к сыну, страдания Евгении Семеновны начинаются с ее веры в политическую идею, а потом уже распространяются на нее самое, ее детей, ее семью, ее жизнь.

Несмотря на то, что «Опустелый Дом» можно отнести к беллетристике, а «Крутой Маршрут» – к документальным воспоминаниям, обе героини, одна вымышленная, другая – настоящая, реагируют одинаково на события сталинского периода. И неосведомленная Ольга Петровна, и осведомленная, с высшим образованием Евгения Семеновна, с той же наивностью не могут поверить, что жестокая действительность сталинщины происходит на самом деле.

Вот первая реакция Ольги Петровны на арест сына: «Нужно было сейчас же бежать куда-то и разъяснить это чудовищное недоразумение». Она уверяет жену арестованного таким же образом директора, что ее сын «не виноват. Он арестован по ошибке».

Евгения Семеновна пишет в предисловии к своей книге: «Основным ведущим (чувством за эти годы) было чувство изумления. Неужели это мыслимо. Неужели это всерьез».

Уверенность, что все происшедшее – ошибка, преобладает и у других. Когда муж Евгении Семеновны, член бюро Татарского обкома партии Аксенов узнает об аресте Биктагирева, 2-го секретаря горкома, он убеждает себя, что это «какое-то недоразумение, временное и даже комичное», и что в отношении его собственной жены «произошла ошибка». Так же воспринимают свое положение Катя Широкова, 18-летняя комсомолка, и Юля Анненкова, бывший редактор немецкой газеты, издающейся в Москве.

И в «Опустелом Доме», и в «Крутом Маршруте» жертвы пытаются объяснить происходящее одной и той же формулой. «Ведь это ясно, что вредители проникли в НКВД», уверяет Таня Крупеник, осужденная на 25-летний срок, «разоблачат их… А мы выйдем». Комсомолец Алик заявляет: «Вредители засели в НКВД – вот и орудуют. Сами они там враги народа».

Обратиться с правдой необходимо к самому Сталину. Ольга Петровна пишет ему личные письма. Алик хочет с ним лично поговорить. А Оля Орловская, сидя в одиночке в Ярославле, пишет Сталину стихи:

«Сталин, солнце мое золотое!»

По крайней мере 20 из 76-ти заключенных, едущих в товарном вагоне из Ярославля во Владивосток, получающих в жару одну кружку воды в день, «с упорством маниаков твердят, что Сталин ничего не знает о творящихся беззакониях», что «надо больше писать ЕМУ, Иосифу Виссариановичу [sic!]… Чтоб знал правду».

Вышеупомянутая Юлия Анненкова считает, что Сталину изменили, что измена проникла «во все звенья партийного и советского аппарата».

Таких иллюзий Евгения Гинзбург не разделяет: «если все изменили одному», возражает она Анненковой, «то не проще ли подумать, что он изменил всем?» Ибо «наивно монархическая идея о добром вожде, не знающем о злоупотреблениях злых чиновников, уже тогда, на ранних этапах моего крутого маршрута, не находила во мне отклика».

И тут «Крутой маршрут» идет дальше «Опустелого дома». Документальные воспоминания Гинзбург, Сталина не боготворящей, но и к оппозиции не принадлежащей, ставят, как говорится, ребром щекотливый вопрос о роли партийца во времена сталинщины. Что случилось? Партия арестовывает своих. Как должен вести себя коммунист в «своей» тюрьме?

Только малая часть партийцев доводит логическую цепь до конца. Но с заключительным выводом и они справиться не могут: Питковская, Коган, Подольская кончают жизнь самоубийством. Мысль о самоубийстве одно время преследует самое Гинзбург.

Вторая, большая часть партийцев, осужденных как и сама Гинзбург по 58-ой статье, продолжает искусственно поддерживать свою партийность, не взирая на окружающую действительность.

Аня маленькая доверяет свои горести со следователями только Евгении Семеновне, «как партиец партийцу», «чтобы не слыхали беспартийные», так как «материала против партии нашей нельзя им давать…»

В товарном вагоне, в котором женщин везут не как людей, а как «спецоборудование», Сара Кригер одергивает другую коммунистку: «не теряй лица, здесь есть беспартийные».

Эти коммунистки, а среди них и сама Гинзбург, не делают окончательных выводов из того, о чем свидетельствуют им факты. Они продолжают верить в абстрактную идею партии, в ее линию: индустриализацию страны, коллективизацию сельского хозяйства (не замечая или не желая замечать, какими методами эта последняя линия проводится на практике…). «Даже сегодня, после всего, что уже было с нами», пишет Гинзбург, разве мы проголосовали бы за какой-нибудь другой строй, кроме советского...?»

Этот логический провал трудно сопоставим с человечностью, господствующей в «Крутом Маршруте», с нравственной чистотой автора. Вопиющая несправедливость и немыслимая жестокость мучений и пыток, своих и чужих, часто заставляют Евгению Гинзбург думать, что она играет роль в кинофильме. И тут же решать – нет, этой действительности в кино бы не поверили. Когда у одиночных заключенных перед этапом отнимают фотоснимки детей, швыряя их в кучу, один из солдат наступает своим тяжелым сапогом на груду этих родных лиц. Если бы какой-нибудь режиссер решился воспроизвести эту картину крупным планом, то, – пишет автор, – критики решили бы, что «это уж слишком!»

То же самое чувство появляется у Гинзбург на пароходе, переправляющем тюрзаковцев в Колыму. В 43-градусной горячке она видит «крупным планом голые ляжки старика, сидящего на параше. Дрожащие, тощие, как у ободранного петуха, покрытые синей кожей…». И спохватывается: «нет, этого, наверно, нельзя снимать, это будет грубый натурализм».

О той же глубокой человечности автора свидетельствует ее юмор. Стоит вспомнить рассказ арестантки Риммы Фаридовой: «Вначале я проходила у них как троцкистка, … но по троцкистам у них план перевыполнен, а по национальностям они отстают».

Или рассказ бабы Насти: «вот и про меня, вишь ты, наговорили и прописали: трактористка. А ведь я, веришь, вот как перед Истинным, к нему, к окаянному трактору и не подходила вовсе».

Или эпизод с воробьями: «На рассвете несколько воробьев, еще не узнавших, очевидно, о том, что "здесь нам не курорт", и что начальник Бутырской тюрьмы Попов категорически запрещает общение птиц с заключенными, бойко взлетели на верхушку деревянного щита».

Но человеческий протест Евгении Гинзбург почему-то останавливается на полдороге. Ее мысленный вопрос в кабинете Ярославского (во время процесса исключения ее из партии): «Почему же ваша ошибка искупается только ее сознанием, а почему я должна расплачиваться кровью, жизнью, детьми?» так и остается висеть в воздухе. На него Евгения Гинзбург, оставшаяся после своего крестного пути коммунисткой, ответа не дает.

А ответ, быть может, найден Таней Станковской, умершей в транзитке: «Из Ярославки взрослыми детьми вышли». Или же Виктором Вольским, в «Искуплении» Даниэля: «За что ты сидел в тюрьме? Ты и 99% всей 58-ой? Вы же сидели ни за что. Вы тоже ничего не делали. Ни плохого, ни хорошего – н и ч е г о…».

· Это миланское издание изумляет исключительной неряшливостью и колоссальным количеством опечаток. Гораздо лучше «Крутой Маршрут» издан в журнале «Грани» №64 (Изд. «Посев» Франкфурт на Майне).

"

“This last year of my first life, abruptly cut off in February of 1937, has been surprisingly contradictory for me,” Evgenia Semenovna Ginzburg writes in her memoirs that were recently published in Milan in Russian under the title Krutoi Marshrut [Into the Whirlwind]. This “chronicle of the cult of personality” describes her second life, in which Ginzburg, an ordinary communist, transforms from “hammer to anvil.”[1]

Into the Whirlwind reminds one of a book by Lydia Chukovskaia previously published in Paris, The Deserted House. At first glance, communist Evgenia Semenovna’s Via Dolorosa appears so distant from commoner Olga Petrovna’s heartache! The former victim is active, while the latter is passive. They are both mothers, but while Olga Petrovna suffers solely from her love for her son, Evgenia Semenovna’s miseries stem from her trust for the political idea, and only then branch out onto herself, her kids, her family, and her own life.

Although The Deserted House is closer to fiction and Into the Whirlwind is more similar to documentary memoirs, both heroines, one fictional, the other real, react identically to the events transpiring during Stalin’s reign. The ill-informed Olga Petrovna and the well-informed and educated Evgenia Semenova are similarly naïve in their inability to believe in the brutal reality of Stalinism.

Take for example Olga Petrovna’s initial reaction to her son’s arrest: “The first thing to do was to run somewhere and clarify this bizarre misunderstanding.” She assures the wife of a director, who was arrested in the same manner, that her son is “not guilty. He has been taken in by mistake.”

In the preface to her book, Evgenia Semenovna writes: “The main (feeling of those years) was the feeling of astonishment. Is this really conceivable. Is this the reality.”

The belief that all that is happening around is but a mistake is prevalent in others as well. When Evgenia Semenovna’s husband Aksenov, a member of the Bureau of the Tatar Regional Party Committee, finds out about the arrest of Biktagirev, the 2nd secretary of the city council, he assures himself that it is “some sort of misunderstanding, a temporary and even a comical one,” and that in regards to his own wife “there has been a mistake.” A similar position is taken by Katia Shyrokova, an 18-year-old Komsomol member, and Yulia Annenkova, a former editor of a Moscow-based German newspaper.

In both The Deserted House and Into the Whirlwind, the victims try to make sense of the events through the same formula. “It is perfectly clear that enemies have penetrated the NKVD,” assures Tania Krupenik, sentenced to 25 years. “They will be exposed, and we will be released.” Komsomol member Alik insists: “Enemies have settled in the NKVD, and now they are in charge. They are themselves the enemies of the people.”

It becomes necessary to let Stalin himself know the truth. Olga Petrovna sends him personal letters. Alik wants to speak with him personally. As for Olia Orlovskaia, she writes him poetry from her solitary confinement cell in the Yaroslavl prison:

“Stalin, my dear golden sun!”

At least 20 out of 76 prisoners, crammed into a freight train car on their way from Yaroslavl to Vladivostok and receiving one cup of water per day in the scorching heat, “reiterate with the stubbornness of maniacs that Stalin knows nothing of the unlawfulness taking place,” that one “needs to write more to HIM, to Joseph Vissarianovich [sic!]… So that he knows the truth.”

The aforementioned Yulia Annenkova believes that Stalin has been betrayed, and that betrayal has penetrated “all the links of the party and Soviet apparatus.”

Evgenia Ginzburg does not share such illusions: “if all betrayed one,” she challenges Annenkova, “then is it not easier to think that one betrayed all?” For “even then, at the early stages of my steep journey, the naively monarchical idea of a great leader being unaware of the officials’ unlawful abuses did not resonate with me.”

It is here that Into the Whirlwind goes further that The Deserted House. The documentary memoirs of Ginzburg, who does not idolize Stalin, but does not belong to the opposition either, bring, so to speak, a delicate question to light about the role of a party member during the Stalinist era. What has happened? The party arrests its own members. How should a communist behave in “his own” prison?

Only a small fraction of party members follow this logic to the end. But even they cannot come to terms with the conclusive findings: Pitkovskaia, Kogan, and Podolskaia all commit suicide. At one point, the thought of taking her life haunts Ginzburg as well.

The other, larger group of party members, convicted, like Ginzburg, through article 58, continue to artificially maintain their loyalty to the party despite the reality that surrounds them.

Little Ania entrusts her sorrows with the investigators only to Evgenia Semenovna, “as one party-member to another,” “so that those who are not in the party do not overhear,” since “they cannot be given any information that can be used against the party.”

On the freight train, in which the women are transported not as people, but as “special equipment,” Sarah Kriger cuts a fellow communist short: “don’t lose face, there are not only party members among us.”

These communists, including Ginzburg herself, do not draw any definitive conclusions from the facts presented to them. They continue to believe in the abstract idea of the party and its line: the industrialization of the country, collectivization of agriculture (not noticing, or choosing not to notice, the methods through which the latter is carried out in practice…). “Even today, after everything that we’ve been through,” Ginzburg writes, “would we vote for any regime other than the Soviet one…?”

It’s difficult to reconcile this logical collapse with the humaneness that prevails in Into the Whirlwind, with the moral purity of the author herself. The flagrant injustice and inconceivable cruelty of torment and torture, whether her own of those of others, often make Evgenia Ginzburg think that she is playing a role in a movie. Only to immediately realize that no, even in a film, such reality would not be credible. When photographs of children are taken away from inmates in solitary confinement and thrown into a pile before they are transferred to the camps, one of the guards stomps on the heap of these dear faces with his heavy boot. If a filmmaker decided to adapt such a scene to the screen, a close-up, the critics, – the author writes, – would say, “that’s too much!”

The same feeling recurs onboard the steamship that transports the prison convicts to Kolyma. In a 43-degree fever, Ginzburg sees “a close-up of an old man’s naked thighs as he is seated on a bucket. Trembling and skinny, like those of a ragged rooster, covered with blue skin…” And she immediately corrects herself: “no, this cannot be filmed, that would be crude naturalism.”

The author's humor speaks of her profound humaneness. It is worth recalling prisoner Rimma Faridova’s story: “At first I was categorized as a Trotskyite… but they had already over-fulfilled their plan for Trotskyites, yet they were still behind in regards to the nationalities.”

Or the tale of grandma Nastia: “and about me too, you see, they’ve spoken things and labeled me: traktorist. While I, believe it or not, hand to God, have never even come close to the damn tractor.”

Or the scene with the sparrows: “At sunrise, a few sparrows (who obviously have not yet been told that 'this is not a resort,' and that Popov, head chief of Butyrka Prison, prohibits any communication between birds and inmates) swiftly flew atop a wooden window shield.”

But for some reason Evgenia Ginzburg’s humane protest ends halfway. The question she asks herself in Yaroslavsky’s office (as she is being expelled from the party) remains hanging in the air: “How come your mistake is atoned by simply admitting it, while I have to pay for mine with my blood, my life, my children?” Evgenia Ginzburg, who remained a communist after her Via Dolorosa, does not provide an answer to this question.

It is possible, however, that the answer is offered by Tanya Stankovskaia, who died in the transit prison: “Out of Yaroslavl Prison, we came out as grown-up children.” Or by Victor Volsky from Daniel’s “Atonement”: “What were you in prison for? You and the other 99% convicted through article 58? You were imprisoned for nothing. You too, did nothing; nothing good, nothing bad –

nothing.”

[1] This Milan edition is astonishing for its extraordinary sloppiness and colossal number of typos. A much better version of Into the Whirlwind is published in the 64th issue of the journal Grani (Pub. Posev, Frankfurt am Maine)

"