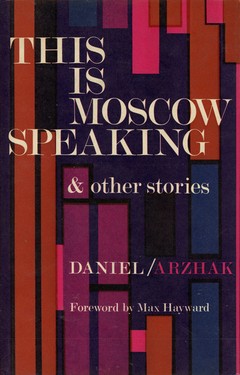

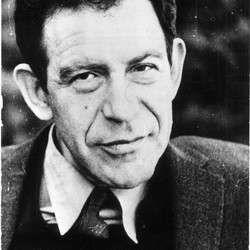

Yuli Daniel, who writes under the name Nikolai Arzhak, identifies himself as a political writer. He is now enduring a hard-labor sentence in a Russian prison camp. Were it not for these facts we would probably not have this small volume of stories.

The stories, though harmless enough from our point of view, do have political implications. The title story, “This is Moscow Speaking,” explores the implications of a mindless adherence to a political regime that demands a blood sacrifice; the story seems to conclude that one is responsible not only for his own conduct, but indirectly for that of the society as well. The other long story of the group, “Atonement,” moves towards the same conclusion: that there is both individual and collective guilt when society perpetrates an injustice. “Hands,” one of the two shorter stories which fill out the volume, is a story of individual guilt not consciously realized. The protagonist has served the state as executioner of political prisoners; though he believed that his acts were for the good of the state, this does not save him from an emotional breakdown and debilitating physical aftereffects. The fourth story, “The Man from MINAP,” is an irreverent spoof of Russian puritanism and official party pomposity. Though Daniel himself did not particularly like the story, it is good fun and without the strained effect of the other three.

“This is Moscow Speaking’ is a gimmick story, but is nevertheless relatively successful. Moscow speaks and proclaims Public Murder Day, open season on anyone over sixteen. Moscow’s reasons are never made clear. Anatoli Nikolayevich, the protagonist and a writer by trade, records his own reactions and those of his friends to the impending event. Aside from making some bad jokes, they think little about it. Then suddenly the implications of public murder become clearer to Anatoli when his mistress suggests that they murder her husband. He is offended enough by the suggestion to want no more to do with her, but he is forced by the incident to confront the question of moral responsibility and public murder. It is a private struggle; his friends either ignore the question or justify the decree as for the good of “our great Party.” One even suggests that it is better than the old days when our political murders were committed in secret. Though little happens on Public Murder Day, Anatoli does reach some personal conclusions. One cannot equate, as did a boy in the street, government decree and conscience. If one loves his country, and Anatoli insists that he does, then he is answerable for its mistakes.

“Atonement” probes with more subtlety the question of individual and societal guilt. It has no initial gimmick like the Public Murder Day of “This is Moscow Speaking,” hence the reader takes it a little more seriously from the beginning. Again the narrator is a sensitive and intelligent observer of life, this time an artist called Victor Lvovich. The question he is forced to confront is the extent of the responsibility of the individual for the political imprisonments of the Stalin era. He is himself accused of having direct responsibility for the imprisonment of an old acquaintance. Though he is innocent of denouncing the man, many of his friends do not believe him and he suffers as though he were guilty. Out of his anguish comes the realization that perhaps he shares responsibility for the entire political situation that fostered the mass imprisonments. Like the protagonist of “This is Moscow Speaking,” he sees the state as morally culpable, and he believes that the individual citizen shares that culpability.

Though Daniel’s stories are openly political and are interesting for that reason, it is also true that they are openly artistic, perhaps too much so. In both the long stories in this volume he handles his narrative well, allowing the story to unfold in the words of a sensitive and articulate protagonist. His dialogue always has substance. (It does, however, suffer in translation. Anatoli, for example, is called a “sissy” by Zoya when he refuses to help her murder her husband.) The incidents of the stories are skillfully juxtaposed; both stories move easily through time toward a climax that grows naturally out of what has come before.

Still, Daniel tries a little too hard; his art is a little too open at times. In “This is Moscow Speaking” he uses too many devices. Aside from the unlikely contrivance of the Public Murder Day, there are poems to introduce each section, and they do not always work well. There are bottles of liquor that seem to Anatoli to be bottled emotions waiting for release. A poster depicts a scene of violence that becomes real. An old man prods Anatoli’s conscience by suggestion that animals have a morality superior to man’s. Some of these devices work better than other, but there are too many of them. One senses that the writer is trying too hard, manipulating his materials until the reader wonders whether he is being manipulated as well. Perhaps it is the social and psychological questions raised in these stories that give them life. The themes of guilt and responsibility are of interest to the American reader as well as to the Soviet court. And perhaps the stories have a special intensity when the reader remembers that Daniel was sent to jail for writing them. But Daniel is more than a political martyr; he is a good writer as well, one who uses narrative point of view skillfully and who combines incidents into a nice unity. The reader has the sense of satisfaction that comes from a well-built story. Perhaps as Daniel becomes a little less self-conscious about his art – and one hopes he has the chance to do so – he will produce something of an even finer quality.