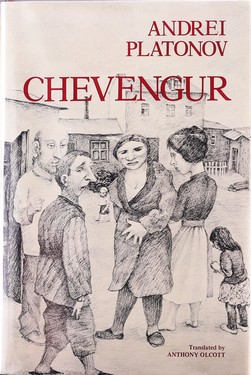

The student of Soviet literature and particularly the devotee of Soviet satire cannot but enthusiastically mark the appearance of translations of the prose of Andrej Platonov (1889- 1951), a writer whose collected works reflect the trends in Soviet satire as dramatically as do the writings of Mixail Bulgakov, Evgenij Zamjatin, Mixail Zoščenko, Vladimir Majakovskij, and others more commonly known in the West. Political difficulties have unfortunately held part of Platonov’s work in abeyance in the Soviet Union and hampered its availability in the West. These new translations mark the first appearance of the unexpurgated texts of two of Platonov’s most devastating satires – his only full-length novel Chevengur and the vitriolic play The Barrel Organ. Collected Works also contains the short novel The Foundation Pit and the short stories The Epifan Locks and Makar the Doubtful (all previously published by Ardis), as well as the short stories The Potudan River, Homecoming, Light of Life, The Cow, The Takyr, The Third Son, Fro, and The City of Gradov.

The choice of texts effectively presents Platonov to the Western reader. The “first publication of Chevengur as an integral unit” (xv) demonstrates Platonov’s affinity with Boris Pil’njak stylistically and ideologically in his assessment of War Communism and the impact of October. The availability of this novel marks a publishing milestone that enhances our assessment of Soviet literature from the Revolution into the period of the First Five-Year Plan. The novel utilizes the rather stock themes of the 1920s: the tribulation and torment of War Communism; the unfeeling communist; the brutality of the Civil War; the political and ideological excesses resulting from the establishment of the new revolutionary order among the provincial masses; the dichotomy between the interests of the simple man and the interests of the Revolution; NEP; and the bureaucracy. The novel is a rather unique panorama of life and of Soviet literature’s perception of it, and is a monument both to and of the decade.

The other works in the collection that can be positively traced to the 1920s establish Platonov as one of the outstanding satirists of the decade in which Soviet satire flourished. The City of Gradov (1926), one of the outstanding exposes on bureaucracy and simplistic ideological pseudo-solutions, The Epifan Locks (1927), which can easily be read as an allegory of October and its implementation as well as an historical novel shrunk in size and dedicated to personal themes, and Makar the Doubtful (1929), a glaring expose of the bureaucracy and the gulf between the reality of October and its ideals, are typical of works written in the 1920s by writers who sensed discord between October’s promises and the reality of contemporary life. The stories demonstrate that Platonov was an important figure in the mainstream of satire, despite the fact that he remains poorly known and generally unappreciated in the West.

The works selected for translation from the 1930s and 1940s illustrate Platonov’s breadth. One finds The Foundation Pit, a soberly satirical work in the spirit of Chevengur, and The Barrel Organ, a work that favorably compares with the drama of Majakovskij, Nikolaj Erdman, and Bulgakov in satirical intensity. These works of sustained grotesque are satirical masterpieces that ran afoul of the censorship. They too explore the panorama of satiric themes found in Soviet satire until the purges of the 1930s: the gulf between the people and the Revolution; the materialistic, rigid communist; the absurdity of the new utopia; bureaucracy; the kulak, religion, and other remnants of the past; and the new Soviet man. These works demonstrate anew how unified the satiric movement was thematically. Lest one consider Platonov exclusively a satirist, and one should note that satire unfavorable to the system often receives disproportionate attention in the West – the editors of Collected Works have included some short stories from the decades of satire’s demise that show Platonov’s sensitivity and talent as a writer of short fiction. The atmosphere and locale are typically Soviet, yet the attention given to personal themes and the individual in his emotional complexity is a departure from the thrust of most writing in the Stalinist years. Reading these stories, one finds a gifted writer of serious fiction whose work compares favorably with popular western writers.

Translating Platonov presents a challenge that has been met very well by Olcott, Whitney, Kiselev, Jordan, Snyder, and Carl Proffer and his Ardis editorial staff. Joseph Brodsky, in his preface to The Foundation Pit, observes that “…Platonov is untranslatable, and in one sense that is a good thing for the language into which he cannot be translated. But nevertheless one has to congratulate any attempt to recreate this language…” (xii). One must indeed congratulate those who labored over a writer in the legacy of the ornamentalist tradition, whose innovations in lexicon, approximation of oral speech and thought patterns, and sudden scenic and thought transitions make him one of the most creative writers of his epoch.

These editions of Platonov are eminently worth having and make a significant contribution to the body of translated Soviet fiction. One laments the absence of a critical introduction to Collected Works while at the same time applauding the introductory remarks of Anthony Olcott to Chevengur. Much could be said in such an introduction about Platonov’s language and style, his works still unfamiliar in the West, his role in the evolution of Soviet fiction, the nature of his links with the Revolution, and the interesting ebb and flow of his difficulties with official and semi-official disfavor, which are replete with critical attacks and recantations and the harassment of himself and his family. Such an introduction would make an excellent volume still better.

Richard L. Chapple, Florida State University