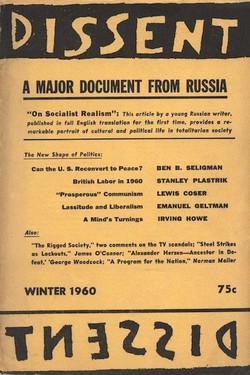

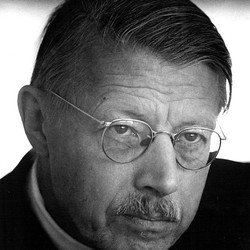

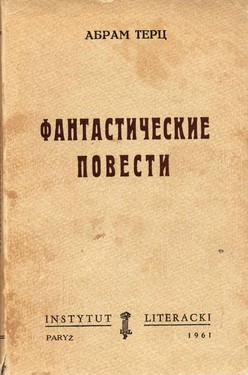

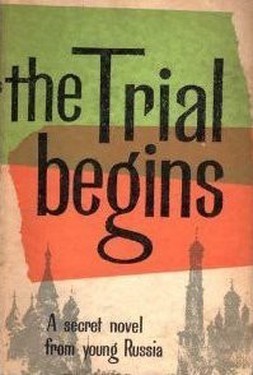

Abram Tertz has already passed into legend. The name, as everyone knows, is the pseudonym of a gifted Soviet writerAbram Tertz, On Socialist Realism, introduction by Czeslaw Milosz (New York: Pantheon Books, 1960). $2,95. Also by Tertz: The Trial Begins (New York: Pantheon Books, 1960); Fantasticheskie povesti [Fantastic Tales] (Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1961); this edition includes the original Russian of the following stories: “Graphomaniacs,” “In the Circus,” “You and I,” “House-Mates,” “The Icicle,” and “The Trial Begins”; “The Icicle,” Encounter, XVIII (February, 1962). , who nevertheless seems to be “one of us” – a critic, an ironist, a detached sensibility, a non-conformist, a Faustian striver in the realm of the creative arts.

One American writer Alfred Kazin in The Reporter, the impressions of a quick trip to Russia still upon him, has tried to picture him as one of those intense sardonic young men in turtle-neck sweaters one meets sometimes in the institutes of the literary cafes and restaurants: Russian rather than Jewish, but quick to pounce on a Jewish pseudonym, seeing in it a proper symbol for what he takes himself to be – a skeptical believer, a stiff-necked prophet, a persecuted cosmopolitan, a scapegoat, a psychic sounding-board of moral catastrophe. I am personally convinced that Tertz is Jewish enough – if not by ancestry, then by profession and temperament. His is a particularly delicate use of paradox and irony as instruments to sustain, not the knowing stare of worldly experience, but of all things, the fresh innocence of a youthful ideal. He does not resemble the Greekified Ecclesiastes, but rather the Book of Jonah, that most Jewish of all stories.

“Ah, if only we had been intelligent enough to surround his death with miracles!” he writes of Stalin:

We could have announced on the radio that he did not die but had risen to Heaven, from which he continued to watch us, in silence, no words emerging from beneath the mystic mustache. His relics would have cured men struck by paralysis or possessed by demons. And children before going to bed, would have kneeled by the window and addressed their prayers to the cold and shining stars of the Celestial Kremlin.

And he mocks even his own irony: “While working on this article I have caught myself more than once dropping into irony – that unworthy device!” Yet he traffics not in mockery, but in the quest for an ideal. Like Ignazio Silone, he is basically a religious man. Unlike Silone, he has not broken with the political form assumed by the dreams of his youth.

For Abram Tertz is not quite “one of us,” though he writes in our kind of language. He is a communist. I doubt if he is a member of the party, and he is clearly no ideologue. His rhetoric glows with his awareness of the horrors of his society:

So that prisons should vanish forever, we built new prisons. So that all frontiers should fall, we surrounded ourselves with a Chinese Wall. So that work should become a rest and a pleasure, we introduced forced labor. So that not one drop of blood be shed, we killed and killed and killed.

And yet, he is a communist. Admitting every disillusion, he nevertheless stands firm on the ground of illusion:

Yes, we live in Communism. It resembles our aspirations about as much as the Middle Ages resembled Christ, modern Western man resembles the free superman, and man resembles God. But all the same, there is some resemblance, isn’t there?

He engages us, this Tertz.

After a long discussion of the religious nature of socialist realism, he attributes its sterility not to intolerance but to eclecticism:

They lie, they maneuver, and they try to combine the uncombinable: the positive hero (who logically tends toward the pattern, the allegory) with the psychological analysis of character; elevated style, declamation, with prosaic descriptions of ordinary life; a high ideal with truthful representation of life. The result is a loathsome literary salad.

In any case, socialist realism as a religious faith could not survive the death of Stalin and the attendant exposures:

The strength of a theological system resides in its constancy, harmony, and order. Once we admit that God carelessly sinned with Eve and, becoming jealous of Adam, sent him off to labor at land reclamation, the whole concept of the Creation falls apart, and it is impossible to restore faith.

Tertz, therefore, favors a “phantasmagoric art, with hypotheses instead of a Purpose.” He does not wish to reestablish a theological system, but merely to catch a glimpse of God, if only of His flashing hind-quarters. By a curious route, art becomes once again an instrument of discovery.

In his fiction, Abram Tertz has no traffic with either the positive hero of socialist realism or with that new hero of sensibility who marks a return to the non-political problematics of normal everyday reality that the greater degree of tolerance since Stalin’s death seems to have inspired in writers like Nagibin and Kazakov. Clearly, his work is still beyond the pale, and it reaches us by devious channels to appear in Paris, London, Rome and New York, but not in Moscow. His writing is original, but not, for us, avant-garde. It bears a striking resemblance to the work of that crushed genius of the Soviet twenties, Yurii Olesha. But Tertz is deeper and surer of himself than Olesha was. His real masters are Gogol and Dostoevsky, and some of his literary creations start from Dostoevsky’s conception of the underground man.

Dostoevsky’s hero lived his life “between the floorboards,” and ventured from there on his catastrophic forays into the conventional world to humiliate himself and to unsettle others; but also to stand hypocrisy on its head, to violate the smugness of accepted routine, to prove – by inflicting pain upon himself and others – the reality of his spiritual existence in a world otherwise indifferent to his precious uniqueness. The underground man, in this desperate assertion of his own individuality, remains incomplete as a man, adolescent; not because he assaults the barricades of convention, but because he refuses to accept responsibility for the suffering of others, upsets lives without participating in them, is incapable of compassion. He has a function, but not a role. One of Tertz’s favorite themes, on the other hand, is the education of the underground man – his growing up to compassion, his assumption of a role.

In the story “Graphomaniacs” the narrator is convinced that he is a great writer. He has trunkfuls of manuscripts – all rejected by the publishing houses. He feels his greatness denied him, while others steal his lines and receive acclaim for them. Meanwhile, he sponges on his wife and bullies his friends. They are “graphomaniacs.” Russia is full of graphomaniacs. The rewards of fame are so great and censorship and intolerance so easy to blame for failure: the graphomaniacs pursue their endless scribbles of absurdity. And he alone is the unrecognized genius, the writer.

At home, the narrator discovers that even his six-year-old son, named after him, has begun to write, has carefully composed a little fairy tale about dwarfs laboring in a forest by a lake. “I think it’s fine,” he says dryly, “that you’ve begun to write…” But adds:

Look. If you want to, copy headlines from the newspapers; copy the titles of books, the names of birds and animals. That won’t do any harm. But why note down every bit of nonsense that comes into your head? Give me your word, Pavlik; don’t do that any more. Don’t make up any more fairy tales about any kind of Lilliputians. It’s dumb and embarrassing. And people will laugh at you and tease you if they find out… When you grow up, Pavlik, and you read the fat books your father composed, you’ll understand that it isn’t a simple matter. You need talent. Maybe even genius. And just think what would happen if everybody started to write? Who would there be to work? Who would do the reading? I mean, if all around there were only writers? I’ll tell you what, we’ll share up equally: I’ll be the writer, and you be an engineer or a musician. Now, remember. Papa’s a writer, and Pavlik’s an aviator. Pavlik’s a regimental commander – the great Colonel Pavlik. Or a sailor. You know what fun that is – ‘over the waves-over the waves-here today-tomorrow there…’

The boy must be discouraged at all costs. Future readers might not be able to tell father from son… The narrator leaves home and takes up residence with another graphomaniac, a poet. The apartment fills with a strange gathering, bemedalled army colonels, pince-nezed Chekhovian types, all sorts – graphomaniacs all – each reading his own work aloud and listening to no one. The narrator is furious. He alone, he insists, is the true writer. The others merely plagiarize his works. They are scoundrels and thieves. But his host addresses him with a prophetic utterance, which he will remember later: “Graphomania is the swamp from which rises the pure spring that will one day cover and refresh the earth.” This is against physics. The narrator leaves in a fury.

Walking the night streets of Moscow, he has a sense of the loads of books on shelves, graphomaniacs working away behind lighted windows, and he begins to feel more and more depressed – no longer a writer of genius, but a graphomaniac himself. He resolves to return home and give it all up. Crossing a bridge, he has a vision – not of writing, but of being written. Something, Somebody, is writing him, and the bridge, and the houses where in that wee hour a few lights still mark the wakefulness of the most desperate of the graphomaniacs. Early in the morning he returns home and gives Pavlik back his crumpled composition. “Write, Pavel, write! don’t be afraid,” he says,

Let them laugh at you, let them call you a graphomaniac. They’re graphomaniacs themselves. All around us – graphomaniacs. There are lots of us, lots of us. More than necessary. And we live in vain and die unimportantly. But some one of us will get through. Maybe you, maybe me, maybe somebody else. He’ll get through, he’ll make it. Write, Pavel; compose your fairy stories about those absurd little dwarfs of yours. And I’ll work on my own… We’ll think up so many fairy stories together… past counting… Only, look here. Don’t say a word of this to Mama.

If the underground man has from the start a desperate sense of his own uniqueness which he asserts not merely against convention but even against reason, Tertz teaches him, also, involvement. It is involvement at the deepest, subconscious level and it can be made manifest only through art.

“The Icicle” is a longer, more complex elaboration of this theme. The narrator’s uniqueness derives from a peculiar metempsychotic gift which informs him he is not unique. He is many people, among them some who have died ages since and who crowd in upon his tormented sensibility. Everything and everyone he looks upon breaks down before his sight into the components of its past and informs him of its future. His gift isolates him. He strikes out occasionally at the world from which he is alienated. But there is a woman he genuinely loves, Natasha, who as a reincarnation of the heroine of Russian nineteenth century fiction represents the aspirations of his youth“For Russian literature they [the women] served as a synonym of the ideal, as symbol of a higher Purpose… And since she [the heroine] occupies, like every Purpose, a passive and waiting position, her beautiful, magical, mysterious, and not too concrete nature permits her to represent a higher stage of the ideal and to serve as a substitute for the absent and desired Purpose” (On Socialist Realism, p. 63).. His gift informs him that she will be crushed by a falling icicle that hangs from a building over a certain corner in Moscow. He concentrates all his powers on saving her from this fate; but to no avail. His gifts prove temporarily useful to the bureaucratic apparatus of military intelligence, but as for Natasha – they only serve to move her more certainly to her doom. And to the consternation of the bureaucrats, Natasha’s doom destroys the narrator’s gift. Second sight leaves him and he can no longer predict the machinations of the C.I.A. or the outbreak of revolt in Africa. He can only express the kind of involvement with the past and future of the world, and with Natasha, that has been his experience, and he can make a work of art of it. He stuffs his narrative into a bottle, like a shipwrecked sailor, hoping it will be discovered and read by someone: by himself in another incarnation, or by his kindred selves who surely exist all over the world.

If the underground man is not Abram Tertz’s only theme, Dostoevsky at least is never far from him. He possesses something of that great writer’s boldness of intellect, which insists on thinking all ideas through to the end; and his people, like Dostoevsky’s, live as they think. Tertz is not a philosopher, but something even rarer: a real writer of ideas.

In “The Trial Begins” he dramatizes the theme of his essay “On Socialist Realism.” It is the relation of means to ends, and the wearing-down, the obliteration of the ends by the means; not merely by “corrupt” means, but by all. The pure adolescent idealist Seryozha defeats his own purpose as surely as his bureaucratic father defeats his, or his sensualist friend Karlinsky. Nevertheless, Seryozha emerges with dignity, while the others, in the failure of their purpose, are crushed.

The novella contains three relatively innocent characters (Seryozha, the Jewish doctor Rabinovich, and the narrator himself) and at the end they are collected by bureaucratic caprice in a forced labor camp. They argue over the significance of a cruciform-handled ancient dagger that Rabinovich has found. For Seryozha, it demonstrates Russian precedence in the discovery of America and should be entrusted to a public museum. For the narrator, it is a potential weapon that must be turned over to the authorities. For the history-wise Rabinovich, it demonstrates the triumph of means over ends – the cross become a dagger. His argument is cut short by the guard who orders them back to work. “We took up our spades as one man.” Their unity is forced; but they have discovered each other.

As a manipulator of paradox, as a stylist, a diamond-cutter of words (which Dostoevsky rarely was) Abram Tertz is not to be underestimated. Nothing quite like him has come out of the Soviet Union to date. There is his magnificent parody of Gogol’s apostrophe to the troika in “The Icicle”; his vision of the rusalki and wood demons dashing away from the industrialization of their native habitat into the overcrowded demon-possessed apartments of Moscow in “House-Mates.” In “The Trial Begins” a lecturer in a planetarium gives a long, dull harangue on how the planets revolve around the sun and not vice-versa, demonstrating that there is no God. But after the lights have been turned on again, an old peasant in a caftan mutters into his beard as he leaves, echoing Galileo: “And yet, there is a God.” The gentle, family-loving Chief Prosecutor gives a party; the guests are all kindly, gentle men; one even knits doilies as a hobby. The vodka flows, they are convivial; but half the world is afraid of them; and they are afraid of each other. As the party goes on, they stare more into their glasses; and finally, they lapse into complete silence. In “House-Mates” and that fantastic study of paranoia, “You and I,” the narrator is literally a demon, addressing the subject he possesses: “Now, you see, I’m a glass on your table. For God’s sake, don’t pour vodka into me, you fool!” His horrors can be Kafka-esque or Gogolian. He can be very funny, and he is endlessly inventive.

Russian or Jew, young or middle-aged, an established literary figure known in the Soviet Union under another name for less bold, less flamboyant stories and articles, or completely unknown to his fellow citizens, an engineer, a factory manager, an ordinary worker, a jazz musician earning his living on the open market of metropolitan night life, a professor of zoology, a school teacher, the curator of a provincial museum, or simply a graphomaniac living off his wife or family – whoever, whatever he may be, Abram Tertz clearly is somebody in his own right. He is also symptomatic of deep changes that have been taking place in the Soviet Union since the death of Stalin.

I cannot quite believe Harrison Salisbury when he tells us in the Times that current literary controversies reflect a fundamental split in the Communist Party itself. Nevertheless, I believe in the significance of the graphomaniacs, and in Abram Tertz, who is not only an extraordinary writer but with absorbing generosity embraces their cause. He represents also our own hopes and fears. That makes him a suitable candidate for legend. I certainly wish him a long and productive life. But if he should die, I think I would seek ways, as he urges, “to surround his death with miracles!” In fact, his life deserves no less.