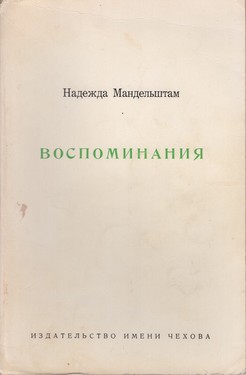

The first post-Stalinist publication in the West of Osip Mandel’štam’s collected poetry by Gleb Struve and Boris Filippov came in 1955. The Chekhov Publishing House volume contained Mandel'štam's previously published but long unavailable poetry and a considerable body of poems not included in earlier volumes. At the time of that publication, Mandel'štam was remembered mainly by specialists in Russian poetry, who thought of him as the third most interesting of the Acmeists, secondary in interest to Gumilev and Axmatova and not to be compared in any meaningful way to the major stars of 20th-century Russian poetry such as Blok or Majakovskij. But the 1955 publication and subsequent ones, which have made available further treasure troves of Mandel'štam's posthumous poetry and prose (and the eloquent essays and memoirs on him by, among others, Il'ja Èrenburg, Anna Axmatova and Marina Cvetaeva), have been gradually but momentously changing our view of this poet's importance, to the point that by now the entire stellar chart of the Russian poetic firmament has been perceptibly shifted and altered by his new-found magnitude. To continue with this astronomic imagery, the present ascent of Mandel'štam's reputation is comparable not to the sudden appearance of a dazzling comet, but rather to the discovery that a major sun has been added to a galaxy and that all the centers of gravity will have to be reconsidered and recalculated.

Since important poets are very much a part of the living literary tradition, estimates of their relative magnitude violate Mandel'štam's own behest: “Ne sravnivaj: živuščij nesravnim.” But it is worthwhile to recall how arbitrary and ill-considered evaluations of Russian poets can be. The contemporaries of the last few years of Puškin's life were quite sure that he had been eclipsed as a poet by Benediktov. Vissarion Belinskij, under the spell of A Hero of Our Time and overlooking such far more deserving contenders as Baratynskij and Tjutcev (their poetry was far too complex for his understanding, in any case), placed the poetry of Mixail Lermontov on a par with that of Puškin, and it remains there today for many people. While Mandel'štam confessed that Lermontov never seemed to him to be Puškin's brother or even his distant relative, such émigré writers as Bunin and Poplavskij are on record as actually preferring Lermontov to Puškin. The generation of the 1860's came to value Nekrasov higher than either Puškin or Lermontov, and their children in the 1880's loved the poetry of Nadson more than that of any other Russian poet who ever lived. The public poll taken on the eve of World War I which, overlooking Blok, Belyj, Xlebnikov, and Axmatova in their prime, proclaimed Igor' Severjanin the poet of the period, and the supreme position accorded today to Evgenij Evtušenko by all lovers of Russian poetry who cannot read Russian are two of the more recent examples, of such facile delusions.

The present, inexorably growing recognition of Mandel'štam's true poetic stature is therefore all the more remarkable. His poetry is genuinely difficult. Totally new and unprecedented in form and content, it lacks the outward trappings of novelty or innovation. As Marina Cvetaeva once pointed out, Mandel'štam's poetry uses a classical form to work its charms and magic. But the chief causes for the delay of full recognition are not really literary. The regime that hounded him and destroyed him physically had also spared no effort to discredit him as a poet. And it nearly succeeded. Just how nearly is shown not only by the statements of that party hack of a poet, Aleksandr Prokof'ev, who supported the post-Stalinist plan to republish Mandel'štam so that the world would see what a poor poet he was, but also by the declaration of none other than Evtušenko himself who, at his memorable appearance at an AATSEEL meeting in New York a few years ago, eulogized Blok, Majakovskij and Pasternak and then regretfully informed the audience that for him Mandel'štam was not a real poet (after which a lady in the audience turned the proceedings into a Theater of the Absurd by informing Evtušenko that "we in America do not know anything by Mandel'štam" and urging him to recite some Mandel'štam for them).

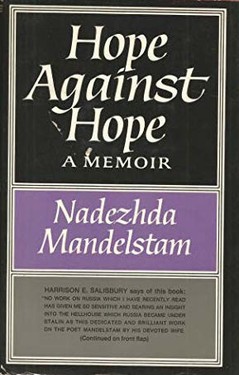

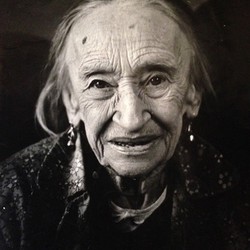

Mandel'štam's persecutors managed to destroy him and to obliterate his reputation but what would appear to be the most vulnerable component of his existence as a poet, the manuscripts of his later magnificent and tragic poems, survived. It was the publication in the West of these hitherto unknown poems that started by now irreversible process of posthumous re-evaluation and of the dawning realization that in Mandel'štam Russian poetry lost its greatest 20th-century poet and one of the very greatest poets that any modern literature has produced. The story and the survival of those manuscripts against incredible odds is told in the memoirs of Nadežda Mandel'štam, the poet's widow, which have been published almost simultaneously in Russian and in English. The book is a record of the poet’s last years (a harrowing ordeal from which death might have seemed a deliverance) and of his wife's efforts – through courage, ingenuity, the help of others and, most of all, sheer good luck – to rescue his writings from destruction until some unimaginable future when they could again become publishable.

Nadežda Mandel'štam herself survived long enough to see the new publications of her husband's poetry (almost everywhere except in the Soviet Union), to read new translations of his work into other languages and the scholarly articles devoted to his work in foreign publications. There is a triumphant note in her book, as there well might be, for this witty and compassionate woman lived to realize an impossible dream for which she had worked against staggering odds for so many hopeless decades. The Soviet literary authorities have been postponing their promised Biblioteka poèta volume of Mandel'štam for twelve years now. In other countries this would seem outrageous, but for Mrs. Mandel'štam this postponement of the inevitable is only an occasion for wry humor.

The English translation of the memoirs, Hope Against Hope, has been widely and favorably reviewed in the American press. It has been praised as a vivid record of life under Stalin, which it certainly is. A nationally syndicated columnist urged that the book be made compulsory reading for today's young militants. The efficacy is somewhat doubtful: a youthful activist advocating with impunity the overthrow of the government cannot possibly imagine a world in which the phrase “I wish I lived in Paris” can lead to a trial for treason and a ten-year hard-labor sentence. Nevertheless, with all the favorable reviews and the publicity that Hope Against Hope has enjoyed, it is sure to contribute to a better understanding in the West of Soviet life and problems.

For those who can read Russian, the original version of the memoirs, Vospominanija, is infinitely preferable. Max Hayward's English translation is certainly adequate, but it does resort to simplifications and abridgments and in general indulges in what Kornej Čukovskij used to call gladkopis'. There is little effort to reproduce Nadežda Mandel'štam's expressively colloquial diction or to explain her numerous literary allusions and quotations. Epithets and qualifications, such as the description of II'f and Petrov as “two young savages,” are casually dropped, and the striking stylistic originality of the Russian text is systematically toned down. Still, the translator's task was a formidable one in this case: Nadežda Mandel'štam has learned a great deal from the incandescent prose of her late husband and she can and does write with considerable brilliance as well as power. Her book is rich in many kinds of rewards for a student of Russian literature and history. Its center is the documentation of Mandel'štam's life and work, but there is also a great deal on other writers: Axmatova, Belyj, Pasternak, Kataev, and other noted figures. There is also a great deal of fascinating material on many other Russians, whose experiences the author observed or shared, well known figures such as Buxarin and Larisa Reisner and unknown people such as her proletarian landlady Tat'jana Vasil'evna or Alisa Gugovna Usova, made unforgettable by the author's account of them and by her literary art.

The importance of these memoirs as testimony and as social history makes their publication a major event in Russian cultural life. The freshness, originality, and literary sophistication with which the book is written place it in the front rank of Russian memoir literature. Nadežda Mandel'štam is not only the courageous widow of a great poet, who managed to save his work for the Russian people and for the world, but a talented and accomplished writer in her own right. Her literary ability becomes fully evident only upon reading the original Russian version of her book. The translated version, however, does offer one valuable dividend: the appropriate and wholly admirable introductory essay by Clarence Brown, the American scholar to whom so many of us owe our awareness of the full extent of Mandel'štam's greatness.

Simon Karlinsky

University of California, Berkeley