The publication in the Soviet Union in 1958 of a collection of Andrej Platonov’s stories and the appearance of several of his stories in periodicals in the last two decades have allowed Soviet Russian readers to enrich their vision of their own literature and to lay claim to Platonov’s stylistic and visionary power as part of their cultural heritage. The publication in English in 1970 of a collection of some of Platonov’s best and most famous stories not only excited appreciation for Platonov as an artist, but also caused Western readers to modify further the standard view of Soviet literature in the 1930’s and 1940’s as a literature dominated almost entirely by works of conventional Socialist Realism.

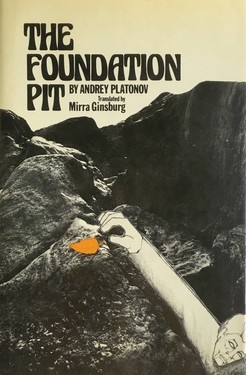

The Foundation Pit (Kotlovan, which is still available in the Soviet Union only unofficially) is one of Platonov’s two novels, and the only one available in its entirety in Russian or English. The two recent English translations of the novel under review here allow Western readers to judge more fully Platonov’s style and the depth of his artistic vision. Written in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, The Foundation Pit shares with many other works of that period a concern with what was seen as the central problem of the new Communist society: the relationship between a collectivistic, materialistic ideal and the spiritual needs of individual human beings. More than in most other works of early Soviet literature, however, the characters in The Foundation Pit seem to be trapped in the world of this problem. In part, the sense of entrapment is the result of the language and the form of the novel. As in the writing of many of Platonov’s contemporaries, especially of Zoščenko, the language in The Foundation Pit is a combination of direct, colloquial Russian, in which the spiritual and physical reality of ordinary people traditionally found expression, and the theoretical, rhetorical language of the Communist ideal, toward which all Russians were supposed to be striving. Platonov’s use of language differs from that of Zoščenko and many other of his contemporaries, however. Though the writing is a conscious literary stylization, there is no sense that the narrator of The Foundation Pit is playing with his language. Rather, as Joseph Brodsky suggests in his introduction to the Ardis edition, the narrator subordinates himself to the language of the novel. The impression of such a subordination is the result partly of the fact that The Foundation Pit is told in the third person, rather than in the first (as are many of Zoščenko’s works, for example). In addition, the narrator makes little use of a light, humorous irony that would suggest a standard of normality and sanity such as would provide an escape from, or a point of view for judging, the oppressive world of The Foundation Pit. Characters are trapped between the everyday language of their reality, which has mainly despair, anger, and longing to express, and the language of the only alternative which their world allows them, the language of the Communist ideal which has little to do with the emotional or physical reality of their lives. Thus the language of The Foundation Pit embodies the dilemma of the characters, and, apparently, of the narrator himself.

Rendering The Foundation Pit into English puts immense demands on the translator, demands of which both Mirra Ginsburg and Thomas Whitney are fully aware. Their methods of creating translations that respond most faithfully to the original, however, differ. Whitney’s translation is the more literally faithful of the two. It reproduces more fully the density and stylized awkwardness of the original, even in those places where the Russian is nearly unintelligible. Ginsburg’s translation, while it is designed to reproduce the peculiarities of the original, reads more smoothly and approximates standard English more closely. A characteristic example of the difference in method between the two translations occurs throughout the novel in the rendering of the highly evocative, but common Russian word, skučno. Skučno occurs repeatedly and sometimes unexpectedly in the Russian text, often to suggest a state of anguish. Its repetition creates a central motif and develops great cumulative power. Whitney consistently translates skučno with the basic dictionary equivalent of “bored” / “boring.” Ginsburg translates it variously as, among others, “sad,” “melancholy,” “boring,” “lonely.” She thus exchanges the cumulative power of repetition for a more exact rendering of the specific emphases of the word in various situations. Whitney chooses to forego the variety of specific emphases for the less precise, but more striking and powerful, effect of repetition. Ginsburg’s translation makes more explicit the range of meanings skučno can have; Whitney’s translation renders more accurately the form and unconventional usage of the original.

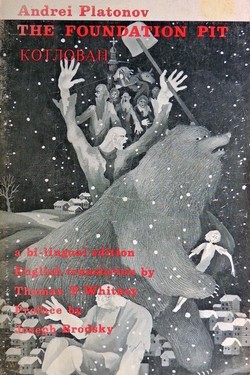

With the exception of a few mistranslations (there seemed to me to be more of them in Whitney’s rendering) and a handful of misprints in the Ardis edition, both translations are basically reliable. The Dutton edition contains a translator’s introduction to Platonov and to the novel, and will appeal most to a general audience. The Ardis edition has the advantage of containing the Russian as well as the English texts, and of including an interesting and provocative introductory essay on the language of the novel by Joseph Brodsky. It thus provides a useful text for courses in Soviet literature, whether taught in Russian or in English, and especially for courses dealing with Modernist and post-Modernist prose, as well as offering an edition of the novel for the non-specialized reader of Russian or English.