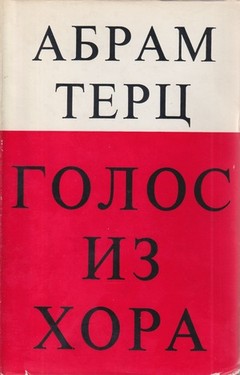

Il libro di transizione di un famoso scrittore russo

ABRAM TERZ

Golos iz chora

Stenvalley Press, Londra, pagine 339, sterline 5

Dal risvolto del volume si viene a sapere che questo è un commiato di Terz dai suoi lettori. D’ora in poi lo scrittore russo – «smascherato» ed arrestato nel settembre 1965, processato nel febbraio 1966, insieme a Daniel e condannato a sette anni di lavori forzati, rilasciato dai campi di Mordovia nel giugno 1971 con un condono di sedici mesi per la buona condotta, autorizzato dal governo sovietico nel 1972, ad andare con la moglie e il figlio a Parigi dove gli è stato offerto un incarico alla Sorbonne – userà il proprio nome e cognome: Andrej Sinjavskij.

Durante la sua prigionia di cinque anni e mezzo Sinjavskij, approfittando dei regolamento carcerari, mandava alla moglie residente a Mosca due lettere al mese, ognuna di circa venti cartelle fitte. Al ritorno si trovò tra le mani un manoscritto di millecinquecento pagine, dal quale con un po’ di fatica era possibile ritagliare tre libri.

Il primo, «Una voce dal coro», appunto, esce adesso a Londra in russo sotto il celebre pseudonimo. Gli altri due, «Passeggiate con Puškin» e «All’ombra di Gogol’», saranno firmati da Sinjavskij restituito ormai, dopo la lunga parentesi della clandestinità e della pena scontata, ai prediletti studi della letteratura russa.

Commiato

È giusto che sia così, perché il commiato di Terz, oltre ad essere un atto puramente formale di voltare la pagina tocca la sostanza della sua esperienza di scrittore incarcerato. SI vuole dire con questo che nei campi della Mordovia l’autore di Entra la corte (pubblicato in Italia da Mondadori), della Gelata e di Lubimov (pubblicato in Italia da Rizzoli), si distacca man mano, si disimpegna davvero da quasi tutto ciò che il suo «sottosuolo» letterario e il suo clamoroso processo hanno rappresentato nel risveglio e nella presa di coscienza del dissenso sovietico. Si assiste insomma, procedendo nella letteratura di Una voce dal coro, ad una autentica e sincera (anche se malinconica e a tratti assai penosa) riconquista della vecchia identità, a uno spettacolo di Sinjavskij che si spoglia coi gesti sempre più risoluti dell’abito occasionale (e logoro, secondo lui) di Terz. In un certo senso quindi è un libro di indubbia onestà: un letterato nato, uno studioso di lettere, si guadagna sotto la pressione delle circostanze, e dopo aver pagato di persona, il diritto di mettere la parola «fine» alla propria sventurata sortita nelle regioni che non gli sono connaturali – come lo sono, poniamo, a un Solgenitsin, a un Sacharov o a un Amalrik – e che per giunta gli sembrano aride o comunque poco promettenti. In un altro senso, però, è un libro deludente: per quanto dotto ed intelligente fosse il Sinjavskij, quali che siano le sue notevoli risorse intellettuali, le doti della sensibilità unite ad una solida cultura, ci si separa malvolentieri dall’estroso, geniale e ribelle Terz. Come se si osservasse addolorati il ritiro di uno scrittore, soppiantato gradualmente da un letterato.

Il libro è composto in maniera da rispecchiare, con la maggiore fedeltà possibile, quella dipartita ineluttabile di Terz. Ogni capitolo corrisponde a un anno di prigionia. Mentre nei primi il Coro – cioè il vociare confuso ma vividissimo dei compagni nella baracca, il racconto smozzicato della Russia in catene – segue la Voce interiore in cerca di solamente, e nel terzo riesce persino a sopraffarla con il suo rombo, cominciando dal questo è la Voce, l’io «stanco degli uomini» e assetato della solitudine, a prendere il sopravvento. Le riflessioni e le divagazioni dell’autore si fanno più lunghe fino a spaziare da sole, Terz nel momento di ritornare Sinjavskij diventa sordo al mondo che lo circonda.

Astrazione

Le cose che ha da dire – sulla letteratura, sull’arte, sulla storia e filosofia, sui suoi profondi sentimenti religiosi e appassionati interessi etnologici – sono di straordinario acume e di grande finezza (si può star sicuri che saranno altrettanto acuti e fini i preannunciati volumi su Puškin e Gogol’). Ma c’è qualcosa di incresciosamente astratto in quella sovranità di chi scrive nei riguardi della realtà attorno. «Che cosa avrei fatto se fossi privato, letteralmente privato, del diritto di scrivere?». La domanda, posta da Sinjavskij a se stesso con una terribile angoscia, significa addirittura voler sostituire alla vita la pagina scritta.

Forse nell’ultimo, brevissimo capitolo di Una voce dal coro, si decantano i termini della situazione in cui si è venuto a trovare Sinjavskij. Liberato dai campi, si sente un morto riapparso nel mondo dei vivi», «uno spettro», «un disseppellito». Confessa di aver scoperto che, per avverare la sua esistenza spettrale, «non ha nessun bisogno degli uomini». Poi chiude il libro con una frase straziante: «E loro (cioè i prigionieri) vanno adesso e vanno, finché vivo qui, finché noi tutti viviamo, loro continueranno ad andare e andare». Per un attimo si vede Terz, all’atto di accomiatarsi definitivamente dal lettore, con la sua doppia ferita: una procuratagli dalla prigionia, l’altra dall’autolesionismo.

Gustavo Herling

The Transition Book of a Famous Russian Writer

ABRAM TERTZ

Golos iz khora

Stenvalley press, London, pages 339, 5 pounds

From the dust-jacket blurb of the volume we understand that this is a farewell from Tertz to his readers. From now on the Russian writer – "unmasked" and arrested in September 1965, tried in February 1966 together with Daniel and sentenced to seven years of hard labor, released from the Mordovia camps in June 1971 with a commutation of sixteen months for good conduct, permitted by the Soviet government in 1972 to leave for Paris with his wife and son, where he was offered a job at the Sorbonne – will use his name and surname: Andrey Sinyavsky.

During the five and a half years of imprisonment, Sinyavsky, taking advantage of the prison rules, sent to his wife in Moscow two letters per month, each of approximately twenty dense pages. Upon his return, he found in his hands a manuscript of fifteen hundred pages, from which, with some struggles, it was possible to extract three books.

The first of these, «A Voice from the Chorus», has now been published in London in Russian under the well-known pseudonym. The other two, Strolls with Pushkin and In Gogol’s Shadow, will appear under Sinyavsky’s own name. He has returned, after the long interruption caused by clandestinity and imprisonment, to his beloved studies of Russian literature.

Farewell

This is fitting, because Tertz’s farewell is not only a formal break but goes to the heart of his experience as a writer in prison. This means that in the Mordovia camps, the author of The Trial (in Italy published by Mondadori), of The Icicle and Lubimov (in Italy published by Rizzoli), slowly detaches and frees himself from everything that his literary "underground” and his clamorous trial represented in the awakening and awareness of the Soviet dissent. As we move through the pages of A Voice from the Chorus, we witness an authentic and sincere (even though melancholic and at times deeply poignant) reclaiming of his former identity, a process in which Sinyavsky sheds, with increasingly resolute gestures, the occasional (and, he feels, worn-out) garments of Tertz.

In a certain way, it is a book of undeniable honesty: a man born to letters, a scholar of literature, who under the pressure of circumstances, and after paying personally, earns the right to put an end to his own unfortunate experience in a realm unfamiliar to him – not unfamiliar to Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov or Amalrik – but which for him seems unpromising. From another perspective, however, it is a disappointing book: despite Sinyavsky’s erudition and intelligence, and his intellectual resources, sensibility and culture, it is hard to part from the fanciful, ingenious, brilliant, and rebellious Tertz. It is like watching, painfully, the retreat of the writer, gradually replaced by the man of letters.

This book is constructed so as to reflect, as faithfully as possible, that inescapable departure of Tertz. Each chapter corresponds to a year of imprisonment. While in the first chapters the Chorus – the confused yet vivid voices of his barrack’s mates, the fragmented tale of imprisonment in Russia – prevails, the inner voice in search of solitude follows close behind, and by the third chapter it even overtakes it with its murmuring. Starting from the fourth chapter, it is the Voice, the self «weary of human company» and drawn to solitude, that emerges. The reflections and digressions grow longer until they stand alone: at the moment when Tertz must become Sinyavsky again, he turns a deaf ear towards the surrounding world.

Abstraction

What he has to say – on literature, on art, on history and philosophy, on his profound religious feelings and passionate ethnological interests – is extraordinarily witty and refined (surely the forthcoming books on Pushkin and Gogol will be likewise). But there is something unpleasantly abstract in the sovereignty of one who writes about the surrounding reality. «What would I have done if I were deprived of the right to write?» Sinyavsky asks himself, with terrible anxiety, a question that means being willing, perhaps, to replace life with the written page.

In the final, very brief chapter of A Voice from the Chorus, Sinyavsky seems to praise his circumstances. Released from the camps, he feels like a «dead man appearing at life’s feast», a «ghost», an «exhumed man». He confesses that he has discovered that, to accept his ghostly existence, «he doesn’t need people». Then he closes the book with a distressing sentence. «But they (the prisoners) will still go on and on. And while I live here, while we all live – they will still go on and on». For a moment, we glimpse Tertz, bidding his readers farewell for good, with his double wound: one inflicted by imprisonment, the other by himself.

Gustaw Herling