Incontro a Milano con Andrej Sinjavskij

Dico a Andrej Sinjavskij: «Vorrei parlare con lei dell’esilio. Dello scrittore e dell’esilio. Pasternak lo considerava un castigo, chiedeva che gli fosse evitato. Scrisse: Sarei nulla lontano dalla mia terra e dalla mia gente. Lei è in esilio. Come vive da esule?».

«Vivo male – è la risposta –. Ma non ho avuto altra scelta. Sono partito perché voglio scrivere. Se non avessi questo compito, non sarei mai partito».

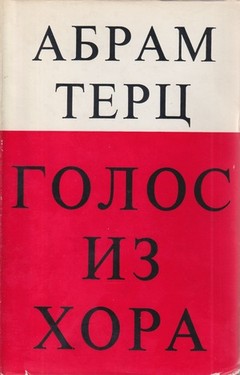

Sinjavskij ieri era a Milano. Esce da Garzanti il suo ultimo libro, Una voce dal coro. Sempre Garzanti pubblica il primo numero di “Kontinent”, la rivista della cultura esiliata o costretta al silenzio. Ricordo alla fiera di Francoforte dell’ottobre scorso la denuncia di Günther Grass. La voce dello scrittore tedesco era agitata. «Dietro Kontinent – gridava – ci sono i soldi di Springer». Springer è il simbolo degli editori di destra. Dal mondo arroccato dei sovietici a un ambiguo impero di carta: il salto, in effetti, è troppo vertiginoso. Come uno slancio innaturale, un’oscura forzatura delle circostanze. L’esilio diventa uno strumento in mani altrui? Questo, per l’edizione tedesca, sembra vero. Ma in Francia “Kontinent" è pubblicato da Gallimard, da noi, come si è detto, da Garzanti. Gli esuli (con Sinjavskij scrivono su “Kontinent” Solženicyn, Maksimov, Brodskij, Nekrasov) sono come una pattuglia in terra di nessuno.

Dico a Sinjavskij: «Perché ha scritto che l’anima stessa dello scrittore tende alla fuga?»

– Il senso di questa frase è molto largo. Ogni forma d’arte, e quindi lo scrivere, è una scoperta, un qualcosa di nuovo che distrugge le norme abituali. Ogni vera opera d’arte ci stordisce sempre e annulla la visione del mondo che si era stabilita prima. Ecco perché parlo di fuga.

– Lei ha anche detto che «lo scrittore è l’alfabeto Morse, col quale i naufraghi di un sottomarino che affonda lanciano i loro messaggi».

– Qui tocchiamo il problema interno della psicologia dello scrivere. La frase va riferita soprattutto alla letteratura russa di oggi, ma credo che riguardi in qualche modo anche le altre. Il processo creativo dello scrittore si effettua in una situazione limite, quasi quella della morte. Per questo mi è venuto in mente il paragone con l'alfabeto Morse e il sottomarino. Lo stimolo che porta a scrivere è una situazione disperata. Non c’è altra via d’uscita, tranne che scrivere.

– Lei afferma di riferirsi anche ad altre letterature. Se ho capito esattamente, la fuga, l'ultimo messaggio, «l’appello instancabile alla verità e alla giustizia senza la speranza di arrivarci mai», per dirla con alcune parole sue, valgono comunque per chi scrive?

– Lo dimostra la storia della letteratura. Essa ci dice che la situazione dello scrittore è quasi sempre una situazione-limite. Conosciamo tanti occidentali che scrivevano e scrivono nella libertà: eppure, nonostante ciò, se sono veri scrittori, la loro è una situazione disperata. Ricorda Joyce? Diceva: quando mi metto a scrivere, mi escono cose proibite. Proibite nel senso più largo del termine. Certo, da noi, in Russia, la condizione è più grave. Da noi la vera letteratura può esistere soltanto se trascende i limiti imposti dallo Stato.

– Julij Daniel fu arrestato e condannato insieme a lei. Daniel ha detto che «benché separato fisicamente dalla sua terra natia, un vero artista è sempre unito ad essa».

– È vero. Vivo in Occidente, a Parigi, ma vivo solo della Russia e per la Russia. Dentro di me nulla è cambiato.

Quando lei arrivò in Francia, nell’agosto del ’73, dopo aver scontato cinque anni di lavori forzati, sul «Monde» fu scritto che «scegliere l’esilio è scegliere la comunicazione delle idee, dello scambio indispensabile tra le culture». È d’accordo?

– Non sono d’accordo. Nell’esistenza stessa della cultura è implicito lo scambio delle idee. Non è necessario l’esilio.

– Che cos’è un libro per lei?

– Le rispondo con le parole di un mio romanzo, La Gelata. La maggior parte dei libri non sono che delle lettere scritte con la memoria del passato e indirizzate all’avvenire. Uno sforzo tardivo per riallacciare relazioni con noi stessi, con i nostri parenti e amici che vivono in noi e sono scomparsi senza lasciar notizie.

– E la letteratura?

– Forse tutta la mia vita è un tentativo di rispondere a questa domanda. D’istinto, potrei dire che la letteratura è una cosa inutile, che si può vivere benissimo senza letteratura, mentre non si potrebbe vivere senza il cibo e senza l’acqua. Mi riferisco non soltanto all’uomo singolo ma anche alla società. Lo dimostra quella sovietica. Ma nello stesso tempo la letteratura è quella cosa inutile grazie alla quale la vita ha un altro respiro oltre a quello del corpo.

– Lei ha firmato finora i suoi libri con lo pseudonimo di Abram Terz. Lo ha fatto perché i suoi libri arrivavano clandestini in Occidente. Ma questo pseudonimo ha un qualche significato?

– Abram Terz è il personaggio di una canzone della malavita di Odessa. Ma non l’ho scelto per questo. Per l’orecchio russo il suono delle parole Abram Terz non è alto, poetico. Pensi al linguaggio dei fumetti: dire Abram Terz è come rendere il gesto di uno che colpisca con il coltello: un colpo breve e violento.

– So che quello che sto per porle è il problema più scomodo. So che nessuno ha il diritto di chiedere a un altro uomo di essere un eroe. Eppure, pensando a lei, a Solženicyn e agli altri esuli, molti sostengono che la nostra vera terra di missione è la Russia, che forse la vostra scelta non è la più giusta. Qualcuno ha aggiunto duramente che i fuoriusciti servono solo a se stessi. Che cosa risponde?

– È una questione importante e complicata. Gli occidentali, quando giudicano i dissidenti e gli esuli, li giudicano come se fossero tutti uguali. Io sono lieto di questo fatto perché dimostra che la Russia può dare tanti scrittori diversi, ma non una sola missione. Ciascuno ha il suo cammino. Non vi può essere una direttiva generale di comportamento. Non si può chiedere a tutti di fare le stesse cose. Non esiste un cammino soltanto eroico. Il disegno della vita e dell’anima russa è molto più complesso.

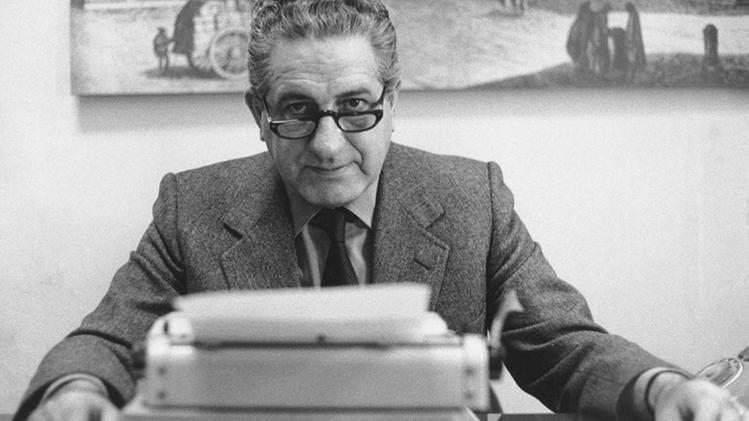

Sinjavskij è un uomo pacato, dalla folta barba di monaco. Ha cinquant’anni e insegna alla Sorbona. Parla soltanto il russo: «È troppo tardi – dice – per imparare altre lingue». Prima di conoscere il campo di concentramento credeva nell’arte fantasmagorica, nel grottesco che sostituisce la realtà. Nel suo mondo di prodigi un critico osservò che «i sogni pittorici di Chagall diventano il paesaggio di ogni giorno».

Proprio dieci anni fa, nel maggio del ’65, uscì in Italia il suo romanzo Lubimov. Ho portato cone me il libro. Sinjavskij ne guarda la copertina che mostra un grosso labero contro il fuoco del tramonto. La guarda e la riconosce: «La prima volta che l’ho vista fu nelle mani del giudice che mi interrogava. Era un corpo di reato». Lubimov è una città immaginaria, più antica di Mosca stessa, dove s’impone un dittatore-mago di nome Lionia. I poteri di Lionia sembrano infiniti: per amor di popolo trasforma le vivande più comuni in cibi raffinatissimi, le acque del fiume in champagne, la sua città in un paradiso. Ma a Lubimov c’è troppo sfolgorio di luci artificiali, gli uomini non son felici. «Tenebre voglio! – grida un personaggio – Ho tanta sete d’ombra».

Fa un effetto strano essere a tu per tu con Sinjavskij. Ricordo i tempi del processo, ma ora è come se le dimensioni eroiche dell’eresia si fossero ristrette. Forse ì vero che il dissenso s’ingigantisce soprattutto quando risuona nelle chiuse terre del dispotismo. La protesta e la denuncia sono ancora dure: ma vengono da qui, non sono più «i segnali di fumo dal cuore d’una riserva impraticabile».

Un’ultima domanda. Chiedo a Sinjavskij se la libertà è difficile. Risponde: «Forse la libertà è la cosa più difficile». Mi vede scrivere la frase, si affretta a chiamare in causa l’interprete. Così non va bene, ci vuole un punto di domanda alla fine. È giusto. L’esilio porta anche dubbi, inquietudini. Riscrivo: «Forse la libertà è la cosa più difficile?»

Giulio Nascimbeni

Meeting with Andrey Sinyavsky in Milan

I say to Andrey Sinyavsky: «I would like to speak with you about exile. About the writer in exile. Pasternak saw it as a punishment, he asked to be exempted. He wrote: ‘I wouldn’t be far from my land and from my people’. You are in exile. What is life in exile like?».

«bad – he answers. – But I had no other choice. I left because I wanted to write. Without that task, I would have never left”.

Yesterday Sinyavsky was in Milan. His latest book A Voice from the Chorus has just been published by Garzanti. Garzanti has also issued the first issue of «Kontinent», the journal of culture in exile or forced into silence. I remember Günther Grass’s denunciation at the Frankfurt Book Fair last October. The German writer’s voice was trembling. «Behind Kontinent – he shouted – is Springer’s money». Springer is the symbol of right-wing publishing. From the sheltered world of Soviet writers to an ambiguous paper empire: the leap is dizzying. An unnatural thrust, a dark coercion of circumstances. Does exile become an instrument in the hands of others? For the German edition, this seems to be true. In France, however, Kontinent is published by Gallimard, in Italy, as noted, by Garzanti. The exiles (Sinyavsky, along with Solzhenitsyn, Maksimov, Brodsky, and Nekrasov, write for the Kontinent) are like a patrol in no man’s land.

I say to Sinyavsky: «Why did you write that the writer’s soul itself tends to escape?»

–– The meaning of that sentence is very broad. Every form of art – including writing – is an act of discovery, something new that destroys habitual norms. Every true work of art startles us; it almost cancels the previously established vision of the world. This is why I speak of escape.

–– You also said that «the writer is the Morse code used by castaways in a sinking submarine to send their messages».

–– Here we touch on the inner problem of the psychology of writing. The sentence refers especially to contemporary Russian literature, but I think it applies to others as well. The creative process takes place in a limit-situation, almost in the presence of death. That is why I thought of the Morse code and the submarine. The impulse that leads to writing is a desperate situation. There’s no way except through writing.

–– You say it applies to other literatures. If I understood correctly, escape, the last message, «the tireless appeal for truth and justice without ever reaching it» – this concerns all who write?

–– The history of literature proves it. It tells us that the writer’s situation is almost always a limit-situation. We know many Westerners who have written and write in freedom. And yet, if they are true writers, their situation is desperate. Do you remember Joyce? He said: When I write, forbidden things come out. Forbidden in the broadest sense of the word. Of course, for us in Russia, the condition is worse. Real literature can exist only when it transcends the limits imposed by the State.

–– Juli Daniel was arrested and condemned together with you. Daniel said that «despite being physically detached from his motherland, a real artist is always connected with it».

–– It’s true. I live in the West, in Paris, but I live only for Russia and of Russia. Nothing has changed inside me.

–– When you arrived in France in August ‘73, after having served five years of forced labor, the Monde wrote that «to choose exile is to choose the communication of ideas, the indispensable exchange between cultures». Do you agree?

–– I don’t agree. The very existence of culture implies an exchange of ideas. Exile is not necessary.

–– What is a book for you?

–– I will answer with the words of my novel The Icicle. Most of the books are nothing more than letters written with the memory of the past and addressed to the future. A late attempt to reconnect with ourselves, with our relatives and friends who live within us and have disappeared without leaving any trace.

–– And literature?

–– Perhaps my whole life is an attempt to answer that question. Instinctively, I would say that literature is a useless thing – one can easily live without it, whereas one cannot live without food and water. And I speak not only of the individual but of society. Soviet society proves it. And yet literature is that useless thing that makes life breathe differently from the body.

–– So far, you signed your books with the pseudonym Abram Tertz. You did that because your books were smuggled into the West. Does this pseudonym have a meaning?

–– Abram Tertz is a character from a criminal song from Odessa. But I didn’t choose it for that reason. To the Russian ear, the sound of the name Abram Tertz is not elevated or poetic. Think of the comic-book language: to say Abram Tertz is like miming a stabbing gesture: short and violent.

–– I know that what I am going to say is the most uncomfortable issue. I know that no one has the right to ask another man to be a hero. And yet, when I think of you, of Solzhenitsyn and of the other exiles, many claim that your true place, your true mission, is Russia, that perhaps your choice was not the right one. Some have harshly said that those who fled are worth only for themselves. What do you reply?

–– It’s an important and complicated issue. People in the West, when they judge dissidents and exiles, judge them as if they were all the same. I am glad in a way, because it shows that Russia produces many different writers, not just one mission. Each one follows his own path. There can be no general directive of behavior. You cannot demand that everyone do the same thing. There is no single heroic path. The pattern of Russian life and soul is far more complex.

Sinyavsky is a quiet man, with the thick beard of a monk. He’s fifty, and he teaches at the Sorbonne. He speaks only Russian: «It’s too late –– he says –– to learn other languages». Before experiencing the concentration camp he believed in the phantasmagorical art, in the grotesque that replaces reality. In his world of prodigy a critic observed that «Chagall’s pictorial dreams become everyday landscape».

Exactly ten years ago, in May ‘65, his novel Lubimov was published in Italy. I have it with me. Sinyavsky looks at the cover showing a big tree against a blazing sunset. He looks at it and recognizes it: «The first time I saw it was in the judge’s hands during the interrogation. It was evidence». Lubimov is an imaginary city, older even than Moscow, where a dictator-dragon named Lionia comes to power. His powers seem infinite: out of love for the people he transforms ordinary food into exquisite delicacies, the river water into champagne, his city into paradise. But in Lubimov too many artificial lights shine, and the people are not happy. «I want darkness! –– one of the characters cries –– I yearn for shadow».

It feels strange to be face-to-face with Sinyavsky. I remember the days of the trial, but now it is like the heroic scale of his heresy seems diminished. Perhaps it is true that dissent grows larger when it echoes within the closed lands of despotism. Protest and denunciation are still harsh: but they come from here – no longer «the smoke signals from the heart of an impassable reserve”.

One last question. I ask Sinyavsky whether freedom is difficult. He replies: «Perhaps freedom is the most difficult thing». He sees me writing and immediately calls in the interpreter. «Not like that, it needs a question mark at the end». He’s right. Exile also brings doubts, apprehension. I rewrite it: «Perhaps freedom is the most difficult thing?».

Giulio Nascimbeni