Chevengur is a remote steppe village where total communism has been organized, where, as one character observes, we did everything first and then read Marx. As a result, life has become much less civilized than it was before the Revolution. The Soviet is installed in the church, and although the local citizenry no longer worry about the Second Coming in each storm or heat wave, members of the Chevengurian bourgeoisie (and “semi-bourgeoisie”) before being shot are given “the entire sky, with all the luminaries pertaining thereto, to be used there as the material from which to organize eternal bliss.” On a Saturday of voluntary labor the village’s houses and yards are repositioned for no good reason, and the question of whether there will be winter under communism is raised and debated.

The only moral protagonist in Platonov’s satiric novel is the orphan Sasha Dvanov; he alone survives. To him belongs the thought: “Communism is the end of history and the end of time, for time runs only within nature, while within man there stands only melancholy.” One is drawn to Kopenkin, a Soviet Don Quixote who on his mighty steed Proletarian Strength tilts against ludicrously tiny provincial bureaucratic windmills designed to achieve communism. But no matter how appealing, for example, his spiritual affection for Rosa Luxemburg – her representation, sewn into his cap, is so beautifully done “that no woman could be compared to her” – no matter how endearing his search for Dvanov and his decision to use Proletarian Strength to plow, Kopenkin is no less brutal and unthinking than the Cadets who mow down the Chevengurians at the end of the novel.

There is an inverted transcendentalism to this extraordinary work: nature, associated closely with humans, has become inanimate. Tinker Zakhar Pavlovich tunes a secret into a piano. Night departs “like cavalry on the fly, and the infantry of toiling, marching day mounted above the earth.” Chepurny, the “Jap” realizes that the proletariat destroys nature with labor. Hunchback Petr Kondaev causes “slight mutilation” in those who torment him. Nature is compared to revolution, not revolution to nature. Added to this is humor conveyed by skaz narration, the malapropisms of simple people bewildered by communist jargon. Soviet knight Pashnitsev guards his World-Wide Communist Memorial National Park dressed in armor and chain mail. Chepurny says that he is “from communism.” In one village local people renamed themselves; there is a Fyodor Dostoevsky, a Christopher Columbus, a Franz Mehring (“Mare”). Klavdusha, as Chevengur’s sole female, is “the raw material for general happiness.” If petit means “petty,” then is not petit bourgeois “a puny kind of business”?

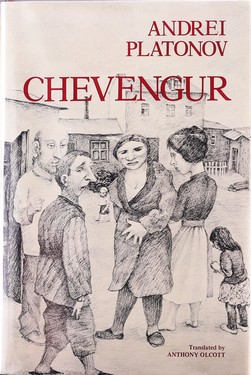

Chevengur is a great piece of literature. Apparently a canonical text is not available, and the translator has attempted to create such a text in his version (the novel, completed in 1928, has never been published in the Soviet Union). There are no chapters, rather odd-length sections separated only by a few asterisks. Perhaps this is appropriate to a novel about historically valid but artificial social divisions. Though once in a great while readers may find Anthony Olcott’s choice of syntax and/or vocabulary objectionable, he has done a superb job of rendering Platonov’s ornamental (parochial, regional, dialectical) prose into English.

Thomas H. Hoisington, University of Illinois