Il sovietico Sinjavskij ha pubblicato tre libri all’estero col nome di Terz - A Mosca lo hanno imprigionato, ma non si sa di quale reato deve rispondere – intanto un suo collega lo stronca per servilismo politico.

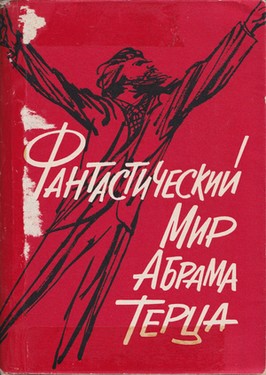

Facciamo un po’ di cronaca. Nell’ottobre scorso lo scrittore sovietico Andrej Sinjavskij viene arrestato a Mosca perché si scopre che ha fatto stampare – col nome di Abram Terz – alcuni suoi libri all’estero. Passano quattro mesi e pochi giorni fa, mentre ancora si attende «una definizione legale della sua colpa», il critico Kedrina sulla Literaturnaja Gazeta lo demolisce: si metta da parte questo vanesio, non vale niente, è uno sporco propagandista-nemico, i suoi simboli, le sue allegorie non hanno nulla di originale.

Il «bel gesto» del Kedrina, che deve essere un arrampicatore ai fasti burocratici, mi ha spinto a vedere di che cosa si tratta. Le tre opere che Abram Terz ha «esportato» sono oramai tradotte in venti Paesi e nella versione italiana hanno questi titoli: Compagni, entra la corte (edizioni del Saggiatore), La gelata e il recente Lubimov (tutti e due editi da Rizzoli); in più si aggiunga un saggio intitolato Che cosa è il realismo socialista, apparso nell’ottobre del ’59 sulla rivista “Tempo presente”.

Anche senza accettare il giudizio perentorio di Mare Slonim, esperto slavista, che considera Abram Terz «il più significativo scrittore sovietico degli anni Sessanta», resta indubitato che la sua presenza ha una vitalità artistica che oggi pochi in Russia posseggono. Prendiamo Evtušenko, un giovane: è una specie di cantautore, legato ad una precisa sapienza di quel che si può dire e di quel che si deve tacere. Prendiamo un vecchio, per di più premio Nobel: Šolochov. Ma è una specie di grossa trebbiatrice ormai superata.

I libri pericolosi

Tra questi poli estremi Abram Terz, sui quarant’anni, è uno scrittore che affronta direttamente una realtà dolorosa con mezzi e modi moderni, di alta letteratura e si mostra originale senza venir meno alle radici del proprio Paese. Per lui hanno fatto i nomi di Gogol’, Dostoevskij, di Belyj, hanno ricordato gli imaginisti e i ničegò. Ma leggendolo a me capitava d’andare più spesso in compagnia di Leskov, quello dell’Angelo sigillato.

Il primo libro, e cioè Compagni, entra la corte, non è certo il migliore scritto da Abram Terz. Segna soltanto la sua vocazione critica nei confronti d’una vita sociale, che conosce da vicino, manovrando con mano pesante su un terreno ben lontano da quello del realismo ufficiale. Questa «opera prima», che risale al 1958, venne presentata come «un esempio esterno, forse testamentario, di quella letteratura del terrore politico e civile, dal quale il mondo è oramai in via di liberarsi del tutto». L’ottimismo di questa affermazione è stato smentito dai fatti e, d’altra parte, già sin da allora l’autore prevedeva che la sua opera sarebbe stata sottoposta ad un’inchiesta perché frutto di «cattive intenzioni e di morbose fantasie».

Lo stesso tema del terrore, diluito in un giuoco del controllo reciproco, si ripresenta nel migliore dei racconti (Tu ed io), che fa parte del volume La gelata, mentre negli altri – che lo precedono e lo seguono – i temi si diramano verso situazioni di piccola quotidianità della vita sovietica. Anche qui, come prefigurazione di cose non poi troppo difficili a immaginarsi, in quello intitolato I grafomani è possibile trovare la chiave del comportamento di Terz nei confronti delle case editrici sovietiche.

Si sa, per sua stessa confessione, che cosa egli voglia raggiungere con i suoi libri. «Essere sinceri – ha detto – con l’aiuto dell’assurdo e del fantastico». Di qui, come corollario, la sua fiducia «in un’arte fantasmagorica, una ipotesi al posto dello scopo, un’arte in cui il grottesco rimpiazzi la descrizione realistica della vita quotidiana». Queste «idee» si vedono portate ad una perfetta riuscita in Lubimov, il romanzo da poco stampato da Rizzoli.

Lubimov è una piccola città immaginaria e sperduta in un qualche angolo della Russia, che non è diventata una grande città «soltanto per sbaglio». Essa, il primo maggio del ’58, cade nelle mani di un «capo» locale, insieme rozzo e illuminato, provvisto d’una strana energia psichica, che ha dello stregonesco: può persino tramutare in vodka una scadente acqua minerale.

La girandola della fantasia scatta in cento direzioni, su molti registri e, certe volte, il colpo finale è racchiuso in una mordente nota a piè di pagina. Il nuovo «capo» di Lubimov agisce, rivolto alla libertà e al progresso, mescolando superstizione con avvenirismo. Fa molte altre cose: sposa un’avventuriera, rivede la vecchia madre, riceve un giornalista americano, trascina dalla sua parte una spia mandata dal capoluogo della regione. E quando guarda la città, può dire alla moglie: «Eccola che giace sottomessa ai nostri piedi. Sottomessa e, al tempo stesso, pensa!, libera e per di più felice, perché io ne regolo desideri e pensieri».

Qualche considerazione

Di questo tono sono le «insinuazioni» che galleggiano sull’intemperante serie di avvenimenti comuni o assurdi che – come acidi rivelatori – servono per intravedere una determinata realtà. La deformazione grottesca, che sconfina col surreale, è intesa anche come valvola di salvezza di un istituto politico. Infatti non c’è mai una affermazione contro il comunismo, e il «discorso» riguarda soltanto la mentalità gerarchica e burocratica nel concepire, a qualsiasi livello, sia la storia, sia il bene del cittadino credulo e indifeso.

È trascorso quasi mezzo secolo dall’instaurazione del regime comunista e questo regime fa gran torto a se stesso se teme l’occhio lucido, la fantasia indagatrice di uno scrittore come Terz; e fa un grande onore a Terz se lo riconosce interprete pericoloso d’una situazione morale e psicologica davvero esistente, tanto da vietarne la conoscenza diretta ai concittadini. D’altra parte il «povero» scrittore, esaurita la denuncia, mostrata la sua verità, non concede la vittoria ai «revisionisti» della immaginaria Lubimov e tutti, in vario modo, verranno travolti e dispersi.

Un nostro scrittore marxista disse, dopo l’epoca staliniana, che dagli scrittori sovietici si aspettava «un’opera veramente tragica, dolorosa, persino crudele». Quest’opera (si risponde così a Pasolini) esiste e supera quelle di un Solzenicyn e dell’ultimo Slonim, che già apparivano come punte coraggiose del realismo-non-ufficiale. Ma chi l’ha scritta è rinnegato dai colleghi ed è imprigionato dai politici.

Enrico Emanuelli

The Soviet writer Sinyavsky has published three books abroad under the name of Tertz – In Moscow he was arrested, but it’s not clear what are the accusations – in the meantime a colleague of his cuts him off for political servility.

Last October, the Soviet writer Andrey Sinyavsky was arrested in Moscow because he sent abroad some of his books – under the name of Abram Tertz – to be printed. After four months, a few days ago, while we are still waiting for a «final legal definition of his negligence», on the Literaturnaya Gazeta the critic Kedrina destroys him: put this vain man aside, he is worth nothing, he is a dirty propagandist-enemy, his symbols, his allegories are nothing original.

Kedrina’s «nice exploit», who must be a climber to bureaucratic heights, prompted me to see what it is all about. The three works «exported» by Abram Tertz are already translated in twenty countries and in the Italian version have the following titles: Compagni, entra la corte (The Trial Begins, Saggiatore editions), La gelata (The Icicle), and the most recent Lubimov (both published by Rizzoli); add to that the essay Che cosa è il realismo socialista (On Socialist Realism), which appeared in October ’59 in the magazine “Present Times”.

Even without considering the peremptory judgement of Mare Slonim, and expert Slavicist who considers Abram Terz «the most significant Soviet writer of the 1960s», there is no doubt that his presence has an artistic vitality that few in Russia possess today. Let’s take Evtushenko, a young man: he is a kind of songwriter, bound by a precise knowledge of what can be said and what must be kept silent. Let’s take an old man, even a Nobel prize: Sholokhov. He is some kind of heavy and outdated threshing machine.

The Dangerous Books

Between these extremes, Abram Tertz, in his forties, is a writer who directly addresses a painful reality using modern means and manners, of high literature, and proves to be original without losing sight of its country’s roots. For him they mentioned Gogol, Dostoevsky, Bely, and recalled the Imaginists and the Nichegò. But as I read it, I often found myself in the company of Leskov, the one of The Sealed Angel.

The first book, The Trial begins, is surely not the best one written by Abram Tertz. It merely marks his critical stance towards a social like, which he knows intimately, wielding a heavy hand in a field far removed from that of official realism This «debut work», dating back to 1958, was presented as «an external, perhaps testamentary example of that literature of political and civil terror from which the world is now in the process of completely freeing itself”. The optimism of this statement has been disproved by events, and on the other hand, even then the author foresaw that his work would be subject to investigation because it was the result of «bad intentions and morbid fantasies».

The same theme of terror, diluted in a game of mutual control, recurs in the best of his stories (You and I), which is part of the volume La gelata (The Icicle), while in the others – which precede and follow it – the themes branch out into situations of everyday Soviet life. Here too, as a foreshadowing of things that are not too difficult to imagine, in the story entitled I grafomani it is possible to find the key to Tertz’s behavior towards Soviet publishing houses.

We know, from his own confession, what he wants to achieve with his books. «Ti be sincere – he said – with the help of the absurd and the fantastic». Hence, as a corollary, his belief in «a phantasmagorical art, a hypothesis instead of a purpose, an art in which the grotesque replaces the realistic description of everyday life». These «ideas» are brought to perfect fruition in Lubimov, the novel recently published by Rizzoli.

Lubimov is a small, imaginary town lost in some corner of Russia, which did not become a big city «only by mistake». On May 1, 1958, it falls into the hands of a local «boss», who is both crude and enlightened, endowed with a strange psychic energy that is almost witchcraft: he can even turn poo-quality mineral water into vodka.

The whirlwind of imagination spins in a hundred directions, on many levels, and sometimes the final blow is contained in a biting footnote. Lubimov’s new «boss» acts with an eye to freedom and progress, mixing superstition with futurism. He does many other things: he marries an adventuress, visits his elderly mother, receives an American journalist, and wins over a spy sent from the regional capital. And when he looks at the city, he can say to his wife: «There it lies, submissive at our feet. Submissive and, at the same time, imagine!, free, and what’s more, happy, because I control its desires and thoughts».

Some thoughts

This is the tone of the «insinuations» that float above the intemperate series of common or absurd events that – like acid revelations – serve to glimpse a certain reality. The grotesque deformation, which borders on the surreal, is also intended as a safety valve of a political institution. In fact, there is never a statement against communism, and the «discourse» concerns only the hierarchical and bureaucratic mentality in conceiving, at any level, both history and the good of the gullible and defenseless citizen.

Almost half a century has passed since the establishment of the communist regime, and this regime does itself a great disservice if it fears the clear-eyed, inquiring imagination of a writer like Tertz; and it does Tertz a great honor if it recognizes him as a dangerous interpreter of a moral and psychological situation that really exists, so much so that if forbids its fellow citizens from knowing about it directly. On the other hand, the «poor» writer, having exhausted his denunciation and revealed his truth, does not concede victory to the «revisionists» of the imaginary Lubimov, and all of them, in various ways, will be overwhelmed and dispersed.

One of our Marxist writers said, after the Stalinist era, that he expected Soviet writers to produce «a truly magic, painful, even cruel work». This work (this is our response to Pasolini) exists and surpasses those of Solzhenitsyn and the late Slonim, who already appeared as courageous exponents of unofficial realism. But the person who wrote it has been disowned by his colleagues and imprisoned by politicians.

Enrico Emanuelli