Yuri Ivask. Review of Venedikt Erofeev's Moskva-Petushki

Руси есть веселие пити! Но в этой пьяной эпопее веселия нет. Есть горе-злосчастье, прикрытое гротескной иронией хотя бы в перечислении фантастических напитков, включающих духи Белая сирень, средство от потения ног, спиртовый лак. Главного героя зовут так же, как и автора, но из этого не следует, что они идентичны. Венедикт-Веничка цитирует Канта и Сартра, Пушкина и Блока. Бродит по Москве, где он только в конце повести увидел Кремль. С вокзала он едет на станцию Петушки. Там будто бы райская жизнь: всегда поют птицы и никогда не отцветает жасмин. Там же живет "любимейшая из потаскух". Здесь, конечно, ирония. Он ведь не верит, что в Петушках "сольются в поцелуе мучитель и жертва" и зло исчезнет. Иногда он кощунствует, иногда молится, и об этом Ерофеев говорит иронически. Саможалости нет. Но есть жалость к другимы – к пьяной и не очень старой бабоньке, которая на все готова за "ррупь". И здесь ирония почти отсутствует. Веничка живет в пьяном аду, как и все его собеседники в Москве и поезде. Трезвых он не встречает. Глядят на него пустые выпуклые глаза "моего народа". В эпилоге появляются четверо хулиганов-пошляков, не прощающих Веничке его отличие от других безмозглых пьяниц: он ведь образован, осмеливается мыслить. Они вонзили шило в самое горло Венички: "И с тех пор я никогда не приходил в сознание, и никогда не приду".

Всякие замысловатые гротески теперь в моде у некоторых писателей и художников, как "внутренней", так и "внешней" эмиграции. Они претендуют на авангардность, но явно не замечают, что их модернизм – залежалый товар почти столетней давности. У Ерофеева таких претензий нет. За его гротесками: острая жалость, невымышленный ужас, жгучая боль и едкая ненависть к советскому казенному лицемерию и советской обывательской пошлятине. Ерофеев остроумен, меток, но всë же его можно упрекнуть в многоглаголании. Зощенко сократил бы повесть вдвое или втрое. Все же, нельзя сомневаться в том, что ему есть что сказать о пьяном горе-злосчастье в Сов<етском> Союзе.

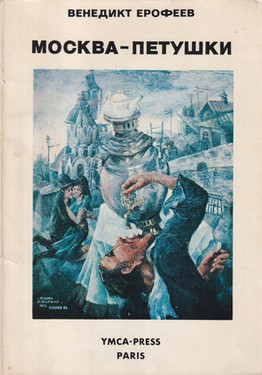

На обложке снимок с картины В. Калинина Жаждущий человек в давно уже знакомом нам стиле раннего голубого Пикассо. Повесть Ерофеева была впервые опубликована в Израиле и переведена на польский язык Шехером и на английский – Тьялзмой.

Юрий Иваск

Happiness in Russia means drinking! But there is no happiness in this drunken epic. There is a woeful evil hidden behind the grotesque irony, if only, as seen in the recital of the extraordinary drinks, that include the perfume White Lilac, Athlete’s Foot Remedy, Alcohol Varnish. The protagonist has the same name as the author, but that does not mean that they are identical. Venedikt-Venichka cites Kant and Sartre, Pushkin and Blok. He wanders around Moscow, only seeing the Kremlin at the end of the story. From the train station in Moscow he travels to Petushki. Life there is, supposedly, heavenly, birds are always chirping and jasmine never stops blooming. There, also, lives his “most beloved of trollops.” This is, of course, ironic, since he does not believe, after all, that in Petushki “will come together in a kiss the predator and the victim” and the evil will disappear. Sometimes he is blasphemous, sometimes he is praying, and this Erofeev also talks about with irony. There is no self pity. But there is a pity for others, for the drunk and not particularly old woman, who will give up anything for a ruble. Here though, the irony is pretty much gone. Venichka is living in a drunken hell, as well as everyone he talks to in Moscow and on the train. He doesn’t meet anyone sober. Looking up at him are the empty, protruding eyes of “my people.” In the epilogue, we see four vulgar hooligans, who do not forgive Venichka his being different from other brainless drunks; he is, after all, educated and dares to think. They stuck an awl into Venichka’s throat, “And since then I have not regained consciousness, and never will.”

All sorts of intricate grotesque techniques are now in fashion among certain authors and artists in both the “internal” and “external” emigration. They are pretending to be avant-garde, but clearly do not notice that their modernism is but a stale product from a hundred years ago. Erofeev has no such ambition. Behind his grotesque techniques is sharp pity, unfabled horror, burning pain and a pungent hatred for the Soviet official hypocrisy and the Soviet commonplace vulgarity. Erofeev is witty, spot-on, but you could still fault him with being too wordy. Zoshchenko would have made this story twice or three times shorter. Still, there is no doubt that he has a lot to say about the drunken, woeful evil in the Soviet Union.

On the cover we see a picture reproduction of V. Kalinin’s painting “Thirsty Man” in an already familiar to us style of the young blue Picasso. Erofeev’s novella was first published in Israel and translated into Polish by Shekher and into English by Tjalsma.

Yurii Ivask